Analyzing Alzheimer’s

Analyzing Alzheimer’s

Author: Mark Parkinson BSPharm: President AFC-CE

Credit Hours 2- Approximate time required: 120 min.

Educational Goal:

To educate Adult Foster Care providers about Alzheimer’s Disease.

Educational Objectives:

Report the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease occurrences.

Explain the disease process and how it progresses.

Define neuroplasticity and cognitive reserve.

Explain different caregiver strategies.

Procedure:

Read the course materials. 2. Click on exam portal [Take Exam]. 3. If you have not done so yet fill in Register form (username must be the name you want on your CE certificate). 4. Log in 5. Take exam. 6. Click on [Show Results] when done and follow the instructions that appear. 7. A score of 70% or better is considered passing and a Certificate of Completion will be generated for your records.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. All procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this article should not be used by care providers without evaluation of their patients’ Doctor. Some conditions and possible contraindications may be of concern. All applicable manufacturers’ product information should be reviewed before use. The author and publisher of this continuing education program have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that all information contained herein is accurate in accordance with the latest available scientific knowledge at the time of acceptance for publication. Nutritional products discussed are not intended for the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of any disease.

Analyzing Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer’s disease is a term that looms large in our caregiving world. Its effects can be seen mainly in geriatrics, but mentally disabled homes and mental health homes may also be impacted. It has been estimated that before you die up to 50 percent of you who are reading this article will develop Alzheimer’s. The other half will be involved in caring for those who do have it. The prevalence of the disease in the general population will double every 20 years until 2040. In certain populations the prevalence is much higher. For example, those with Down syndrome, if they live long enough, may suffer with Alzheimer’s too. Why does Alzheimer’s disease happen? Why do residents act differently? Why do some get the disease while other don’t? Why does it happen later in life? It is my belief that if caregivers know the “whys,” they will be much better caregivers.

I feel obligated to tell you that Alzheimer’s disease is a very complex condition and we just haven’t figured out all the “whys” yet. I have researched the subject and condensed my findings into a form that I think you can digest. If what I write seems a bit off medically, remember this article is a compilation of ongoing research. Our understanding is going to change. Please look at the overall picture I’m trying to paint and use that knowledge to make your caregiving that much more powerful.

What we know so far….

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institute of Health, “Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks.” In essence, brain function is altered because either the brain cells lose their connection to each other or the brain cells have died. It starts with a few cells here and there, and slowly progresses until the ability of the brain to function properly is ruined.

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institute of Health, “Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks.” In essence, brain function is altered because either the brain cells lose their connection to each other or the brain cells have died. It starts with a few cells here and there, and slowly progresses until the ability of the brain to function properly is ruined.

According to the NIA again, “In most people with Alzheimer’s, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. Estimates vary, but experts suggest that more than 5.5 million Americans may have Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer's disease is currently ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, but recent estimates indicate that the disorder may rank third, just behind heart disease and cancer, as a cause of death for older people.”

What Causes Alzheimer’s?

Inside the Brain

Ultimately, Alzheimer’s disease is the result of the loss of brain tissue. To understand why this happens we must go over a little bit of the anatomy and physiology of the brain. The business of the brain happens between cells called neurons. Neurons have multiple branches extending out of them called dendrites. The dendrites stretch out to other neurons, coming very close but always leaving a tiny gap. The gap is called a synapse. When the brain functions, electrical signals flow down the dendrite branches to their end. When the electrical signal reaches the synapse, chemicals called neurotransmitters are released and they flow across the gap. The chemical molecules fit into special receptors on the receiving dendrite, which causes another electrical charge. That charge then flows down to the next neuron, and the signal is passed on.

After a certain point in our development the brain does not make any new neurons, but the brain tissue continues to expand. The individual neurons continue to grow, adding more and more dendrites with more and more synapses. As our brains learn to do things, new neural signaling pathways are built through the new dendrites and synapses. To help keep the neuron healthy the brain has two additional types of cells: astrocytes and microglia. They help clear away debris from between neurons and defend against bad things that could damage the cells of the brain. These cells are vital because once a neuron dies, it is gone forever.

Anything that interferes with the function of these cells would lead to signal transmission malfunction. Events like glucose metabolism problems (glucose is the preferred fuel of the brain), blood circulation issues (getting the fuel to the cells and clearing out waste), toxic chemicals (like alcohol, paint fumes, and lead), respiration difficulties, and age and health of the neuron can all have an effect on how many signals make it across the synapse.

Fortunately, we have billions of dendrites and trillions of synapses in our brain. If a dendrite fails, a synapse misfires, or even if an entire neuron dies, the brain can find an alternative path around the problem. It takes a lot of signal problems to cause functionality issues. Unfortunately, have enough of these malfunctions and the brain can’t find a detour path. That is when you start getting the outward signs that something is going wrong.

The clinical indications of signal transmission failures are:

- Memory loss

- Declining muscle control

- Confusion

- Behavior changes

- Paranoia

- Disorganization

- Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Acting out (lack of inhibitions)

- Cognitive decline

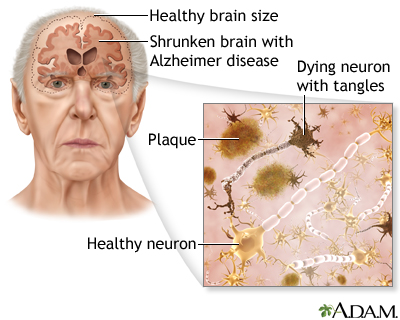

Changes to the Brain in Alzheimer’s

In 1906 Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist, looked at the brain of an elderly female dementia patient who had died. Upon close examination he found many abnormal clumps and unusual tangles of tissue present. He started to see these same odd structures in other dementia patients. He published his research and his finding was used to identify similar dementia cases around the world. Today we identify the abnormal clumps as amyloid plaque and the unusual tangles as neurofibrillary or tau tangles. After over a hundred years of research there are still many unanswered questions, but we have made great strides in our understanding of the disease that Dr. Alzheimer first described.

Amyloid Plaque

When an electronic nerve signal reaches a synapse, it is stimulated into releasing its neurotransmitter chemicals. One of those chemicals is a peptide molecule called a beta amyloid. Beta amyloids can hang around in the synapse and over time start to collect and stick together. The microglia cells, which have been described as the brain’s janitor, are supposed to clear out the beta amyloids from the synapse. If it fails in its job, the peptide molecules ball up together and form a clump so large that the synapse can no longer function. This takes a long time to happen. It is estimated that it takes about 10–15 years for plaque to build up big enough to cause problems on the microscopic level. If you’re 40 years old, you probably have some plaque hanging around as a normal part of growing older. It’s really no problem for the brain; it just sends the signal around the plaque.

In Alzheimer’s disease it is guessed (there is still some debate over the particulars) that when the amyloid plaque fills up a certain amount of the synapse, the microglia cells kick into overdrive and start releasing chemicals designed to clear out the plaque. Those chemicals work too well and clear out some of the synapse structure itself, causing permanent damage.

Tau Tangles and Inflammation

Somewhere during these intracellular events a transport protein called tau becomes super phosphorylated. Never mind the details—just know that when this happens, they become entwined and get tangled up. The tangle is toxic to the cell and can damage the neuron further. Eventually the microglial chemicals stimulate the astrocytes to get involved. They in turn try to contain the problem area through an inflammation reaction. If inflammation carries on too long, it also causes damage to cell structures. The culmination of all these harmful events overwhelms the repair mechanisms of the neuron. The dendrite shrinks, the synapse no longer functions and the neuron dies. When enough damage has occurred to the brain, the classic clinical dementia symptoms of Alzheimer’s start to appear.

The Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease

No one knows yet why the Alzheimer’s disease process starts. For the vast majority it happens later in life and is categorized as late-onset Alzheimer’s. It is most likely the result of a combination of issues that cause plaque to form. Typically, the plaque starts to form while the patients are in their mid- to late forties. Clinical symptoms start to manifest themselves in the patient while they are in their sixties. For the unlucky few, it can happen much earlier in life and is categorized as early-onset AD. Early-onset AD probably occurs because of a genetic mutation. Usually Alzheimer’s-disease-caused brain damage starts in the hippocampus, the portion of the brain involved in memory formation. As the disease progresses, more and more areas of the brain are affected, and the brain loses significant mass.

Not everyone who has amyloid plaque and tau tangles develop dementia symptoms. It could be argued that you really don’t have Alzheimer’s disease unless dementia starts to manifest itself. There are a number of factors that contribute to the development of dementia.

- Genetics – There are several inheritable traits that can increase the chances of developing dementia symptoms, in particular

the gene apolipoprotein E (APOE). A variant APOE ε4 is associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s. There is also evidence that points to spontaneous gene mutations that can lead to the disease.

- Health – Conditions that put a strain on the neural system can speed up the development of mental problems. Obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, alcoholism, and the like may lead to dementia.

- Lifestyle – Poor nutrition, lack of physical and mental exercise, and little or no social interaction leads to a lack of dendrite and synapse development. This creates a low mental capacity reserve which is easy to overwhelm when plaque starts to form. (There’s less capacity to create detours around the problem.)

Stages

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease gradually worsen over time, eventually ending in death. The rate at which the disease progresses varies between individuals. The average time a person lives after an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is four to eight years. My father, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, lived another 20 years. Because the disease can last so long, they have broken up its progression into stages.

Preclinical (no signs or symptoms) – The beginning changes to the brain start to occur on the microscopic level. Beta amyloid is starting to build up in the synapse.

Mild (early stage) – The patient can still function independently, but the outward signs are starting to appear. Memory loss, trouble finding the right word, misplacing objects, etc. Amyloid plaque has started to block messaging pathways. The hippocampus has started to lose function and short-term memory suffers.

Moderate (middle stage) – The requirement of extra caregiving becomes prominent in the life of the patient. Dendrites and synapses have been destroyed and the brain starts to lose significant mass.

Severe (late stage) – The patient loses the ability to respond to their environment, creating a need for a greater level of nursing care. The neurons themselves have died by this point.

Rarely do victims die from a lack of brain function. They usually die from some other cause. My father died from an MRSA infection and the lack of desire to live. At the time he was confined to a bed in a nursing home with little or no recognition of visitors.

Questions Still Remain

We have learned a lot about Alzheimer’s, but several mysteries still remain. There are multiple examples of patients not fitting the typical disease profile. For example, there are plenty of people with the APOE gene that do not develop the disease. Also, there are those who have amyloid plaque and tau tangles but can function independently up until their death due to other causes. It may be due to healthy lifestyle choices, greater brain system development, or some yet-to-be discovered trait.

Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Reserve

A leading predictor of patient functionality despite disease indicators is the concept of neuroplasticity and of cognitive reserve.

- Neuroplasticity – “The brain's ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neuroplasticity allows the neurons (nerve cells) in the brain to compensate for injury and disease and to adjust their activities in response to new situations or to changes in their environment.” Source medicinenet.com

- Cognitive reserve – “The extent to which the brain can sustain damage, as from Alzheimer's disease, stroke, alcohol overuse and head injury, without affecting intellectual capacity.” Source https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/cognitive+reserve

In my opinion, it comes down to the brain’s ability to reroute itself around the Alzheimer’s damage. It has been shown in studies that people with high literacy, educational levels, and social interactions tend to have a higher-than-average ability to avoid the functionality problems of the disease.

Caring for Alzheimer’s Patients

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but there are medications and therapies that can help retain normal brain function longer. They are most effective if applied in the early stages of the disease. So where does that leave the residential caregiver in a care home? In my opinion, your good caregiving techniques can have the greatest impact on the development of the dementia symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Even if you are not taking care of a diagnosed Alzheimer’s patient, all your residents need careful monitoring for symptoms, serious mental stimulation, physical activity, a healthy diet, and proper medication management as part of your basic care. That includes developmentally disabled homes and mental health homes whose residents may be in greater danger of developing AD later in their life.

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but there are medications and therapies that can help retain normal brain function longer. They are most effective if applied in the early stages of the disease. So where does that leave the residential caregiver in a care home? In my opinion, your good caregiving techniques can have the greatest impact on the development of the dementia symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Even if you are not taking care of a diagnosed Alzheimer’s patient, all your residents need careful monitoring for symptoms, serious mental stimulation, physical activity, a healthy diet, and proper medication management as part of your basic care. That includes developmentally disabled homes and mental health homes whose residents may be in greater danger of developing AD later in their life.

In regard to Alzheimer’s, the underlying care concepts that need to be applied to all your residents are: 1. developing greater brain function capacity, 2. recognizing disease symptoms as soon as possible, and 3. once diagnosed, retaining functionality for as long as possible. I put up my mother’s caregiving efforts as proof of concept. She recognized the symptoms early, kept my father physically healthy and socially active, and managed his medications very well.

Developing Greater Brain Capacity

I must admit, development of the brain is a challenging care concept in a care home. You’re not a school, and fortunately you don’t have to be. There are plenty of things you can do in a care home that stimulate the mind. Here are a few ideas that you could easily use at any home.

- Reverse the sedentary tendencies of your residents. Schedule regular walks, trips, and activities. Encourage outings with family. Get exercise equipment for your home. Involve your residents in the chores of the house.

- Provide mental stimulation. Watching TV is okay but there is so much more you can do. Get a playback device with headphones for the residents’ use. Today there are so many choices: smart phones, iPads, laptops, cassette recorders, and mp3 players. For those devices, get audio books, music collections, games, and other such programs. You don’t even have to buy them in some cases. Many residents have monthly allowances that just accumulate, and family members are just looking for things they could give their loved one as gifts.

- Keep the residents from getting into a rut. Schedule a variety of activities and have a ready supply of options to choose from. Get a puzzle table, subscribe to magazines, establish a small library, supply hobby materials, provide letter-writing materials, get pets, make a garden, etc.…

- Change up the environment to exercise the senses. Make a big deal of holidays with decorations. Plan special meal nights. Provide a variety of smells. Provide room plants and floral arrangements. Use and change up table centerpieces.

If this sounds like a lot of work, it’s really just a matter of planning and using the resources at hand. Libraries, the Internet, and thrift stores can reduce the costs.

Recognizing the Early Symptoms

There are plenty of lists out there that itemize all the early Alzheimer’s symptoms. Here is one from the Mayo Clinic:

- Depression

- Apathy

- Social withdrawal

- Mood swings

- Distrust in others

- Irritability and aggressiveness

- Changes in sleeping habits

- Wandering

- Loss of inhibitions

- Delusions, such as believing something has been stolen

The problem with these lists is that most of the items on them are also the normal signs of aging. How can you tell if it’s Alzheimer’s or not? My answer has always been, “When in doubt, send them out.” (To the doctor, that is.) But, I understand your reluctance to go through the effort. It can be upsetting to the resident and the family, not to mention annoying to the doctor. Here is where you can apply what you have learned in this lesson.

Alzheimer’s is a “diseased-caused” loss of brain function that results in abnormal brain function. It is a brain that is starting to have difficulty rerouting its signals around a damaged area. It’s not forgetting where the resident placed their dentures, it’s finding the dentures tucked in a sock drawer. It’s not having difficulty writing down an address, it’s looking at the pen and asking what it’s for. It’s not forgetting a name, it’s forgetting a person. Look for the un-usualness of the behavior and the inability to function appropriately. Make notes and put them into a file. Then send off the file to the doctor with a request for a diagnosis.

Diagnosis

There is no one test that can definitively point to a diagnosis of AD. The doctor must look at all the signs and evaluate the whole person. As a professional caregiver it would be good for you to be prepared for what may come up at the doctor’s office. Being prepared will help you gain the cooperation of the resident during the exam.

The doctor’s evaluation may include:

- Medical history – The doctor will ask about family histories, other recent illnesses, medications, other signs or symptoms that may be occurring.

- Physical exam – The doctor may examine the patient and perform some tests. He will be trying to rule other causes of memory loss and dementia that might be causing the mental problems. The doctor will be looking for anemia, infection, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, certain vitamin deficiencies, thyroid abnormalities, and problems with the heart, blood vessels, and lungs. The doctor will be asking a lot of questions that the caregiver should be prepared to answer. If a family member is transporting the resident, then the doctor’s questions need to be anticipated and the answers need to be written down in the file that is sent with the resident.

- What kind of symptoms have you noticed?

- When did they begin?

- How often do they happen?

- Have they gotten worse?

The Alzheimer’s Association has a great doctor visit checklist. I recommend you use it. Click on the link or copy and paste it in your Internet search field.

https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/doctor-visit-checklist.pdf

- Neurological exam – The resident’s brain functionality with be evaluated. The doctor may look for signs of strokes, Parkinson's disease, tumors, or fluid accumulation on the brain. He or she will be looking at the resident’s reflexes, coordination, muscle tone and strength, eye movement, speech, and sensation patterns.

The doctor may perform mental status tests (Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and the Mini-Cog test). They are designed to test a range of everyday mental skills. The answers can be scored, which gives the doctor an objective evaluation of mental function. An MMSE score of 20 to 24 suggests mild dementia, 13 to 20 suggests moderate dementia, and less than 12 indicates severe dementia. The doctor may use computer programs that perform the same function.

- Advanced testing – If required, the doctor may perform genetic testing that looks for things like the APOE gene. They may also perform brain structure examinations with an MRI, CT, or PET machine.

Medications

There are two considerations with regards to drugs and Alzheimer’s disease: quality of life and behavior control. If you can’t cure the disease or even slow it down, then it comes down to making the most of what remains for as long as possible.

- Brain functionality – There are two types of medications: cholinesterase inhibitors (Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne) and memantine (Namenda). They help reduce cognitive symptoms (memory loss, confusion, and problems with thinking and reasoning) in the early stages of the disease. In short, they help the synapses pass on signals until they get too damaged to function. Caregivers should watch for nausea, appetite loss, bowel movement changes, and headaches. If there is a sudden increase of dizziness or confusion it might be the medication.

- Sleep cycles – Getting the days and nights mixed up is a common feature of AD. In addition, many medications used for behavior control have daytime drowsiness effects, which adds to the problem. The caregiver will have to realize that sleeping aids will not solve the problem, just help manage the situation. Watch for grogginess that leads to agitation and falls that in turn lead to broken bones.

- Behavior control – Here again, caregivers must understand that there are no drug solutions to dementia behavior problems, just tools to help manage them. The brain matter is gone and no amount of drugs will bring it back. These drugs need to be used with skill and close monitoring of side effects. Most have the potential of causing worse problems than the ones they are intended to help with, including death. Don’t be surprised to find a doctor reluctant to prescribe them. Many of the following drugs will be familiar to you so don’t fall into the trap of trying to find a cure for the problem because they worked well in other cases.

Behavioral Medications:

|

Antidepressants- for low mood and irritability

|

citalopram (Celexa) fluoxetine (Prozac) paroxetine (Paxil) sertraline (Zoloft) trazodone (Desyrel) |

|

Anxiolytics- for anxiety, and restlessness |

lorazepam (Ativan) oxazepam (Serax) |

|

Antipsychotics- for hallucinations, delusions, aggression, agitation, hostility, and uncooperativeness

|

aripiprazole (Abilify) clozapine (Clozaril) haloperidol (Haldol)* olanzapine (Zyprexa) quetiapine (Seroquel) risperidone (Risperdal) ziprasidone (Geodon)

|

*special note on Haldol – haloperidol takes up to four hours to see its full effect. Be careful with PRN re-dosing to avoid overmedicating the resident.

Caregiving Techniques

The resources for Alzheimer’s caregivers have greatly improved over the last 20 years. When I was running my adult foster care homes the only resource we had was to send them to a nursing home. We could also put a bell on the front door, so you could catch them before they wandered off. Now you’re positively flooded with courses, advice, ideas, and regulations. To help you utilize all this good input I recommend establishing a caregiver tool box. Think of all the good advice as tools of the trade. Write them down in a notepad, just a short description that helps remind you of the main principles. You could also collect the entire  article and file it in a file drawer. As with any set of tools, one must maintain them and refresh your memory on how to use them from time to time. Here is my contribution to your tool box.

article and file it in a file drawer. As with any set of tools, one must maintain them and refresh your memory on how to use them from time to time. Here is my contribution to your tool box.

Caregiver Mindset

A lot of caregiving in adult foster care homes is based on the active cooperation of the resident. If the resident becomes uncooperative, you try to gain their cooperation through reasoning and techniques that rely on the resident’s comprehension of the situation. I like to call it “motherly bossing.”

Motherly bossing only works so far in Alzheimer’s disease. Why? Because the disease process is preventing the thought signals from getting to where they are supposed to go. The Alzheimer’s resident mentally can’t cooperate like your other residents because they physically have lost the ability to do so. Caregivers will have to develop a new mindset: “Effect behavioral changes by controlling the environment more than controlling the patient.” The more advanced the disease process, the more you’ll have to rely on “manipulating” the resident to behave appropriately. In a nutshell: Do not confront; divert instead.

What does that mindset of caregiving look like? Here are few examples:

- If the resident says, “The sky is red,” you say, “What a lovely shade you have discovered. Let’s celebrate your discovery. Let’s go get a cookie.” The resident then concentrates on getting to satisfy their appetite, not getting stressed out because of the hallucination.

- If the resident tries to wander off, divert their attention by saying, “It’s much too cold to go out without a sweater. Go find a sweater to put on.” Of course, before you give that assignment, you place all the sweaters where only you can find them. When they give up searching for the sweater, pull one out and take a walk with them.

- Decorate with relaxing perpetual motion items like a fish tank. The resident then can watch the fish instead of causing trouble.

- Avoid stress through relaxing music and aromas.

- Get the resident something to take apart. Something to occupy their mind and time with.

- Have patience and let the disruptive behavior run its course. If it’s safe to do so, let them act a little off-kilter. I know it’s annoying, but you will be less stressed if you stop trying to make the resident do what they mentally can’t do.

- Keep track of events that triggers disruptive behaviors and purposely control them. For example, provide a place where visiting children can play away from the Alzheimer’s patient.

Conclusion

The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the population, coupled with the disruptive nature of dementia and memory problems, makes this a major issue in care homes. Care providers will find themselves better able to cope with the demands of care that will be asked of them if they understand the disease and the limitations it causes the resident. Every resident in a care home will find benefit in serious mental stimulation to build mental reserves. Medications can help retain mental functionality in the early stages of the disease. In the later stages of the disease controlling the environment will be more useful in caregiving than controlling the resident.

As always Good Luck in Your Caregiving Efforts.

Mark Parkinson BSPharm

References:

Caregiving for Person with Alzheimer's Disease or a related Dementia. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/alzheimer.htm

Alzheimer’s and Dementia Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association. 2018. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/facts-figures

Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet. NIH Publication No. 16-AG-6423. https://order.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-09/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet.pdf

Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. National Institute on Aging, NIH. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers

Lisa Genova. What you can do to prevent Alzheimer's. Ted Talk Vancouver BC. April 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twG4mr6Jov0

Richard Mayeux and Yaakov Stern. Epidemiology of Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Aug; 2(8): a006239. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3405821/

Alzheimer’s and Dementia. Alzheimer’s Association. 2018. https://www.alz.org/alzheimer_s_dementia

Cognitive Reserve. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/cognitive+reserve

Exam Portal

click on [Take Exam]

Purchase membership here to unlock Exam Portal.

|

|

|

|

|

*Important*

Registration and login is required to place your name on your CE Certificates and access your certificate history.

Username MUST be how you want your name on your CE Certificate.

| Guest: Purchase Exam |