Autism’s Change to Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism’s Change to Autism Spectrum Disorder

Author: Mark Parkinson BsPharm: President AFC-CE

Credit Hours 3- Approximate time required: 180 min.

Educational Goal

Show how the grouping all the different kinds of Autism into a single diagnosis effects Autism therapy.

Educational Objectives

Explain how the various autism disorders are now combine into a single diagnostic category as a spectrum of disorders and its impact on therapy and diagnosis.

Define Autism Spectrum Disorder, and inform about its biology, prevalence, risk factors.

List Autism Spectrum Disorders signs and symptoms and therapy option

Show how ASD effects all foster care settings.

Provide caregiver perspectives on ADS care.

Procedure:

Read the course materials. 2. Click on exam portal [Take Exam]. 3. If you have not done so yet fill in Register form (username must be the name you want on your CE certificate). 4. Log in 5. Take exam. 6. Click on [Show Results] when done and follow the instructions that appear. 7. A score of 70% or better is considered passing and a Certificate of Completion will be generated for your records.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. All procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this article should not be used by care providers without evaluation of their patients’ Doctor. Some conditions and possible contraindications may be of concern. All applicable manufacturers’ product information should be reviewed before use. The author and publisher of this continuing education program have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that all information contained herein is accurate in accordance with the latest available scientific knowledge at the time of acceptance for publication. Nutritional products discussed are not intended for the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of any disease.

Autism’s Change to Autism Spectrum Disorder

This topic was requested by a developmentally disabled caregiver. Yes, I do respond to requests. Just shoot me an email.

Over the past decade, there has been a fundamental shift in how autism is perceived and cared for. Historically, the lack of therapeutic and care options shunted autistic patients into long-term care institutions. Institutionalization hid the problem behind whitewashed walls and created a stigma in the mind of the general public. Autism became a topic of pity that was best avoided in general discussions. In the medical community, all of that has changed. Institutionalization has been largely abandoned in favor of integration. Emphasis has changed from assigning a diagnostic label to developmental therapeutic options. Before we talk any further about this change, we first have to get everyone on the same page.

Autism’s Definitions

No, that is not a typo — I do mean definitions, plural. Let me explain. The general definition of autism is a developmental disorder where the individual has difficulties with social interactions and communicating with others. It often creates restrictive or repetitive behaviors. But there is a problem with that definition. It doesn’t describe the disorder; it’s just a broad list of symptoms. There is nothing beyond calling it a “developmental disorder.” This left the general public, doctors, and even researchers to fill in the blanks themselves, creating, in effect, multiple definitions of what autism is.

Previously, groups of individuals with similar symptoms and severities were placed in the same general subgroup. You probably recognize some of their names: Asperger syndrome, Rett syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD) and pervasive developmental disorders not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), also called atypical autism.

The problem was that the subgroups were very fluid. It seemed that each doctor had their own criteria for who belonged in which group. The confusion was understandable. There is still no clear answer to what causes autism. Even in recognizing the symptoms there is a large variation in severity and presentation. Diagnosis was very difficult for doctors because it was impossible to set clear diagnostic guidelines that everyone could agree upon. For example, Asperger’s syndrome is generally recognized as a milder form of autism. Where does Asperger’s end and autism begin? Which symptom do you measure for severity that indicates it is no longer Asperger’s, but full-blown autism? If you have no answers, many doctors trying to diagnose their patients didn’t either.

In order for that system of diagnosis to work, a lot of effort had to go into finding out what caused the symptoms and trying to find ways to measure them. Many people thought that required too much emphasis on describing symptoms, at the expense of providing meaningful therapy. Labeling different groups of patients also created social stigmas that hampered therapy. Clinicians and specialists started to take a different approach and more effort was concentrated on therapeutic options, regardless of symptoms. Some experts even speculated that autism might be just a natural variation of brain development and not a disorder at all.

A Change in Emphasis

In May of 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DMS-5) removed the individual listings of the various autism disorders and placed them in the general category of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This created a whole new diagnostic model. It recognizes that the level of disability and the combination of symptoms varies tremendously from person to person. It enabled doctors to diagnose patients who may look very different when it comes to their behaviors and abilities but still fit into the same general autism criteria. In my opinion, statements made on the website helpguide.org capture the spirit of this new diagnostic model:

“Autism is not a single disorder, but a spectrum of closely related disorders with a shared core of symptoms. Every individual on the autism spectrum has problems to some degree with social interaction, empathy, communication, and flexible behavior. But the level of disability and the combination of symptoms varies tremendously from person to person. In fact, two kids with the same diagnosis may look very different when it comes to their behaviors and abilities.”

“No diagnostic label can tell you exactly what challenges your child will have. Finding treatment that addresses your child’s needs, rather than focusing on what to call the problem, is the most helpful thing you can do. You don’t need a diagnosis to start getting help for your child’s symptoms.”

What We Know of Autism so Far

I hope that everyone reading this course is on the same page now, or least getting there soon. That is also, in essence, the best way to describe what change has happened to autism care in America today. By describing autism as a spectrum of conditions, the researchers, doctors, therapists, educators, politicians, family members, and caregivers are all on the same page. We are all focused on helping the autistic patient have the best possible outcomes, regardless of what caused the condition to develop in the first place. From now on, when I talk about autism, I mean autism spectrum disorder. Okay, let’s continue. If autism is not a single disease but a spectrum of different conditions, what do we know so far?

Biology

The cause of autism is not well understood. There appear to be many factors that contribute to its development. There may even be several different conditions originating from different biological pathologies that happen to result in the same core autistic symptoms. What is clear is that it is related to changes in the normal maturation process of the brain and nervous system. It may be related to mutated genes (a weakness in the gene expression that causes errors in building brain tissue), a change in how the nerves of the nervous system connect to each other along synapses, physical damage from toxins or inflammation to the pregnant mother and child, or some combination of all of the above.

The cause of autism is not well understood. There appear to be many factors that contribute to its development. There may even be several different conditions originating from different biological pathologies that happen to result in the same core autistic symptoms. What is clear is that it is related to changes in the normal maturation process of the brain and nervous system. It may be related to mutated genes (a weakness in the gene expression that causes errors in building brain tissue), a change in how the nerves of the nervous system connect to each other along synapses, physical damage from toxins or inflammation to the pregnant mother and child, or some combination of all of the above.

There is some evidence that the bacteria in the gut may play a role in autism. The bacteria in our gut is called our microbiome. Research shows clear evidence that our microbiome affects the enteric nervous system, which is connected to the gut-brain axis. Studies are being conducted in hopes of determining if the right balance of microbes in the gut will have an effect on the development or therapy of ASD.

Prevalence

The number individuals who have been identified with ASD seems to be a bit hazy. That is to be expected when you change diagnostic procedures. Its prevalence seems to be increasing, but that just might be related to the new diagnostic methodology. Wikipedia reported estimates of a prevalence of one or two per 1,000 for autism and close to six per 1,000 for ASD as of 2007. Later in the same article it was cited that a 2016 survey in the United States reported a rate of 25 per 1,000 children for ASD. In 2014 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sampled eight-year-old children from 11 U.S. communities and estimated that one in 59 children were identified with ASD.

- Genetics: There is a strong genetic influence on the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). ASD traits are inherited in the vast majority of cases. Parents who have a child with ASD have a 2 to 18 percent chance of having a second child who is also affected.

- Race: ASD appears in all races, ethnic, and socio-economic groups.

- Gender: There are four times the number of boys affected by ASD than there are girls. The reason for this is unclear.

- Age of parents: The children of older parents are at greater risk for ASD. This is because the biological systems of the parents are wearing out, causing errors and mutations.

- Abnormal genetic disorders: People with conditions such as Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and Rett syndrome are more likely than others to have ASD.

- Development at time of birth: Very low birth weight is a known factor in autism.

- Environmental factors: There seems to be an increase trigger of ASD if the pregnant mother has an infection with inflammation (German measles), has taken medications that cause birth defects (antiseizure meds), or has been exposed to certain air pollutants or toxins such as alcohol.

- Vaccination: Vaccinations do not cause autism. There was an attempt to sue a drug manufacturer, claiming a

preservative in a vaccine had caused autism in a patient. It was later proved that the case was a fraudulent attempt at getting rich. After 20 years of extensive research by several organizations, it is clear that vaccinations have no connection to ASD.

preservative in a vaccine had caused autism in a patient. It was later proved that the case was a fraudulent attempt at getting rich. After 20 years of extensive research by several organizations, it is clear that vaccinations have no connection to ASD.

Signs and Symptoms

As we have discussed already, autism is a highly variable brain development issue. Each patient will have their own unique set of symptoms and severities. The impact on the patient’s life is described as low functioning to high functioning. Symptoms can be diagnosed as early as two years old or go undiagnosed until later in life.

WebMD.com states that “half of parents of children with ASD noticed issues by the time their child reached 12 months, and between 80% and 90% noticed problems by two years.”

According to the DSM-5, (the guide created by the American Psychiatric Association used to diagnose mental disorders), symptoms are broadly described as:

- difficulty with communication and interaction with other people,

- restricted interests and repetitive behaviors, and

- symptoms that hurt the person’s ability to function properly in school, work, and other areas of life.

What does all that actually look like in real life? What are restricted interests? What are some examples of individual behaviors that impair the ability to function in life activities? There are many examples, which we can break up into two categories.

Social Communication Problems and the Lack of Social Understanding

- Fails to respond to his or her name or appears not to hear you at times.

- Resistance to being touched. For example, resists cuddling and holding and seems to prefer playing alone.

- Doesn't speak or has delayed speech development. May lose previous ability to say words or sentences.

- Can't start a conversation or keep one going; only starts one to make requests or label items.

- Speaks with an abnormal tone or rhythm and may use a singsong voice or robot-like speech.

- Repeats words or phrases verbatim but doesn't understand how to use them.

- Doesn't appear to understand simple questions or directions.

- Doesn't express emotions or feelings and appears unaware of others’ feelings.

- Inappropriately approaches a social interaction by being passive, aggressive or disruptive.

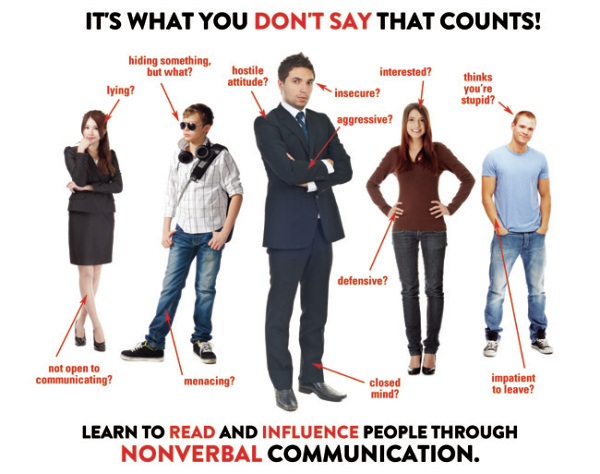

- Unusual or inappropriate body language, gestures, and facial expressions. For example, avoiding eye contact or using facial expressions that do not match with what he or she is saying.

- Problems with pronouns (saying “you” instead of “I,” for example).

- Lack of interest in other people or in sharing interests or achievements. For example, doesn't point at or bring objects to share interest, like pointing at a bird.

- Difficulty understanding other people’s feelings and reactions and recognizing social cues like body postures and tone of voice.

- Difficulty or failure to make friends with children the same age.

Restrictive and Repetitive Behavioral Problems

- Performs repetitive movements, such as rocking, spinning, or hand flapping.

- Not using or rarely using common gestures (pointing or waving), and not responding to them.

- Performs activities that could cause self-harm, such as biting or head-banging.

- Has a strong need for sameness, order, and routines. For example, lines up toys, or follows a rigid schedule. Gets upset by change in their routine or environment.

- Has problems with coordination or has odd movement patterns, such as clumsiness or walking on toes, and has stiff or exaggerated body language.

- Is fascinated by details of an object, such as the spinning wheels of a toy car, but doesn't understand the overall purpose or function of the object.

- Doesn't engage in imitative or make-believe play.

- Fixates on an object or activity with abnormal intensity or focus. For example, has an obsessive attachment to unusual objects (rubber bands, keys, light switches).

- Has specific food preferences, such as eating only a few foods, or refusing foods with a certain texture.

- Repeating words or phrases over and over without communicative intent.

- Taking what is said too literally, missing humor, irony, and sarcasm.

- Delay in learning how to speak (after the age of two) or doesn’t talk at all.

- Is unusually sensitive to light, sound, or touch, yet may be indifferent to pain or temperature.

A Change in Method

I hope you have realized by now that the switch from autism to ASD has turned everything on its ear, medically speaking. Everything is handled differently. You’re not looking for disease markers but how regular abilities are developing. Therapy can and should happen before a diagnosis is made. Therapy concentrates on behavioral adaptation and skill development, not “curing” the disease. A special education teacher may have more impact than a doctor does. So, where do you start? It starts by suspecting something is not quite right and climbing up the ladder. It’s going to take time, patience, and a different mindset.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be a difficult and trying experience. There are no tests to take or biological markers to look for. Diagnosis is based on the presence of multiple symptoms that disrupt a person’s ability to communicate, form relationships, explore, play, and learn. This takes time and experience on what to look for. It may take years of observation by a team of specialists before you can get an official declaration of identification. After all, we’re talk about infants and 2-year-olds who do not communicate normally. It’s going to take extra time observing behaviors and brain development patterns over multiple doctor visits. Diagnosis typically is a two-step process.

Step 1: Well Child Developmental Screenings

What doctors are looking for are delays in regular development. Each child is different but the general guidelines are:

- doesn't respond with a smile or happy expression by six months.

- doesn't mimic sounds or facial expressions by nine months.

- doesn't babble or coo by 12 months.

- doesn't gesture — such as point or wave — by 14 months.

- doesn't say single words by 16 months.

- doesn't play "make-believe" or pretend by 18 months.

- doesn't say two-word phrases by 24 months.

- loses language skills or social skills at any age.

Step 2: Targeted Evaluation

This step is where an “observation team” goes to work. The team might include a child psychiatrist or psychologist, pediatric neurologist, developmental pediatrician, and a speech pathologist. If you are thinking this is starting to look expensive, it is. It is not unusual for medical bills to start topping $60,000 a year.

Associated Medical Conditions

Autism doesn’t occur in a bubble. Other conditions called comorbidities can occur at any time in the child’s life, even up into adulthood. Often, they are linked to the same developmental issues. The strain of trying to live with a disability can also lead the patient into other mental health issues and the development of maladaptive behaviors. Up to three-quarters of ASD patients have comorbidities that reduce their quality of life and hamper therapeutic efforts.

Comorbidities and maladaptive behaviors often seen in ASD are:

- Anxiety and phobias

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Bipolar disorder

- Clinical depression

- Down syndrome

- Fragile X syndrome

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (IBS, constipation, sensitive stomach)

- Intellectual disability and developmental delays

- Motor difficulties (lack of muscle control leading to being clumsy)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Self-injury

- Seizures and epilepsy

- Sleep problems (getting to sleep, staying asleep, nightmares)

- Tantrums

- Tourette’s syndrome

- Tuberous sclerosis

Prognosis

There is no cure for ASD but there is the ability to adapt to the limitations of the disability. Skills can be learned, and therapy can be applied. There are even reports that some children improve enough to lose the ASD diagnosis. Language skills are usually developed by age 5, and other symptoms become less severe as they age into adulthood. The presence of therapy, social support, and gaining a marketable skill are key factors in a positive outcome.

A Change in Therapy

In standard medical practice you usually wait for a diagnosis and then apply therapy to resolve the medical issue. Historically, that didn’t work very well with autism. Even today, there is still no medical intervention that can alter the course of autism. Instead, experts suggest that therapy begin even before a diagnosis is pronounced. They point out that waiting years for a doctor can waste valuable time in the critical years of childhood development. But if there is no medical intervention that can change the course of the disorder, what does autism therapy do?

Goals of Therapy

The shift in focus from identifying the symptoms to therapeutic intervention changes the goals of therapy. The main goals in treating children with autism is to enable functional independence by developing life skills, lessening the associated deficits, and reducing patient and family stress. Even if independence cannot be fully achieved, an increase in the quality of life is still the goal by teaching patients how to accomplish activities of daily living.

What does that look like?

Being a spectrum of disorders, there is no one therapy that works for everyone. A care plan that is tailored to the individual needs of the patient will have to be developed. It will be a long-term plan that changes as the child’s needs change. The guiding principles of the care plan are:

Comorbidity Control and Symptom Impact Reduction

Once comorbidities and troublesome symptoms have been identified, medical intervention can be selected and applied. Medication and therapy can help manage the problems so that the patient can get on with their life.

Early Intervention Services

Early intervention can greatly improve the child’s ability to learn and develop the basic functional and social skills that are needed by every child.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) says that children under the age of 3 years (36 months) who are at risk of having developmental delays may be eligible for special services. These include therapy to help the child talk, walk, and interact with others. Even if the child has not been diagnosed yet, early intervention treatment services may still be available.

Treatment Selection

There are a wide variety of treatment modalities available. Due to the individualistic nature of the disorder, it is impossible to say which is the most effective therapy. Monitoring for effect will be an essential component of therapy. To help you get an overall understanding of the various therapies available, I have combined the choices into the following categories:

These are programs that attempt to modify behaviors through communication therapies and techniques. Behavioral and communications approaches have been around since the 1960s and have been extensively studied. Several different methodologies have been developed.

I found a brief description of several different approaches on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/treatment.html

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

A notable treatment approach for people with ASD is called applied behavior analysis (ABA). ABA has become widely accepted among healthcare professionals and is used in many schools and treatment clinics. ABA encourages positive behaviors and discourages negative behaviors in order to improve a variety of skills. The child’s progress is tracked and measured.

There are different types of ABA. The following are some examples:

- Discrete Trial Training (DTT)

DTT is a style of teaching that uses a series of trials to teach each step of a desired behavior or response. Lessons are broken down into their simplest parts and positive reinforcement is used to reward correct answers and behaviors. Incorrect answers are ignored.

- Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention (EIBI)

This is a type of ABA for very young children with ASD, usually younger than 5, and often younger than 3.

- Pivotal Response Training (PRT)

PRT aims to increase a child’s motivation to learn, monitor their own behavior, and initiate communication with others. Positive changes in these behaviors should have widespread effects on other behaviors.

- Verbal Behavior Intervention (VBI)

VBI is a type of ABA that focuses on teaching verbal skills.

Other therapies that can be part of a complete treatment program for a child with an ASD include:

Developmental, Individual Differences, Relationship-Based Approach

(DIR; also called “Floortime”)

Floortime focuses on emotional and relational development (feelings, relationships with caregivers). It also focuses on how the child deals with sights, sounds, and smells.

Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication-handicapped Children (TEACCH)

TEACCH uses visual cues to teach skills. For example, picture cards can help teach a child how to get dressed by breaking information down into small steps.

Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapy teaches skills that help the person live as independently as possible. Skills might include dressing, eating, bathing, and relating to people.

Sensory Integration Therapy

Sensory integration therapy helps the person deal with sensory information, like sights, sounds, and smells. Sensory integration therapy could help a child who is bothered by certain sounds or does not like to be touched.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapy helps to improve the person’s communication skills. Some people are able to learn verbal communication skills. For others, using gestures or picture boards is more realistic.

The Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)

PECS uses picture symbols to teach communication skills. The person is taught to use picture symbols to ask and answer questions and have a conversation.

If you would like to know more about these therapeutic approaches, visit the Autism Speaks or Autism Society websites, where you can read more about them.

- Dietary Approaches

Dietary approaches assert that some autistic behaviors are a result of food allergies or sensitivities. By reducing or eliminating the offending food, negative behaviors are more easily controlled. For example, if an autistic child has celiac disease (sensitivity to wheat gluten) and is given some bread, then the child will misbehave because his or her stomach hurts.

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Up to 30 percent of parents look outside traditional medical practice for therapeutic options. In desperation, they turn to practitioners of homeopathy, naturopaths, and Eastern medical practices. There is little scientific data on the viability of these approaches. They may or may not work, and they may or may not be safe for the child. As primary caregivers you may have the opportunity to talk to the family about such choices. Tell them that finding a way to measure positive and negative outcomes are critical in these approaches. Point out that when making this choice they are in essence doing a medical experiment on their child. They might believe the myth that because a medical supplement claims to be “natural,” it is safe. Reminded them that deadly nightshade is also “natural,” but is it safe? Here are some examples of good and not-so-good complementary and alternative therapies.

May have some benefit and are relatively safe:

- Creative therapies – Art or music-focused therapy. The goal is to reduce the child's sensitivity to touch or sound by creating enjoyable experiences with these activities. These therapies are usually added on to other treatments.

- Sensory-based therapies – There is an unproven theory that people with autism spectrum disorder have a sensory processing disorder that causes problems in tolerating or processing sensory information. Therapists use brushes, squeeze toys, trampolines, and other materials to stimulate and desensitize these senses. Research has not yet shown these therapies to be effective, but it's possible they may offer some benefit when used along with other therapies.

- Massage — Massages are relaxing and a positive experience. Everyone likes a massage. Unfortunately, there isn't enough evidence to determine if it improves symptoms of autism spectrum disorder.

- Pet or horse therapy — Pets can provide companionship and recreation to any child. Research is just starting to look into whether the interaction with animals can specifically affect the symptoms of autism.

May not be harmful but studies are not conclusive if they are of benefit yet:

- Vitamin supplements and probiotics — Vitamins and probiotics (good bacteria) are not harmful when used in normal amounts. The problem is that no one knows how much and which ones may be of benefit in autism therapy. It also may benefit only certain types of patients, for example, probiotic use for patients that have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). More research is needed.

- Acupuncture — Acupuncture has been used for centuries but its effectiveness in autism is not supported by any significant research.

May be potentially dangerous therapies:

- Chelation therapy — This treatment attempts to remove heavy metals such as mercury from the body. There's no known link between autism spectrum disorder and heavy metals. Chelation therapy for autism spectrum disorder is not supported by any research evidence and can be very dangerous. There are reports that children treated with chelation therapy have died.

- Hyperbaric oxygen treatments — Hyperbaric oxygen is a treatment that involves breathing oxygen inside a pressurized chamber. This treatment is expensive and there is little evidence that it is effective. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved its use in autism.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) infusions — The FDA has not approved immunoglobulin products for this use. This is a flat-out dangerous experiment with no research to support its use.

Autism’s Change and Caregiving

We’ve talked a lot about how the change from autism to autism spectrum disorder has affected medical practice, from managing a disease to therapeutic developmental support. Let’s now talk about what that means to in-home caregiving. As a disease, caregiving was just doing what the doctor ordered. As a therapeutic developmental support, in-home caregiving takes on a more important role in therapy. How you set up your home and how the autistic resident lives there becomes therapy. Let’s talk about ways to make that happen more easily and be more effective. First, let’s make this real for all caregivers regardless of what kind of home they work in.

Missed Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis

I know that there are some adult foster care providers who are in geriatric or mental health homes reading this course and thinking this is just for developmentally disabled (DD) homes. I’m not so sure of that. Not too long ago, some kids who would be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder today might have been labeled as “difficult” or “learning disabled,” and may not have gotten the help they needed. They struggled through life not quite able to make it on their own, and they eventually end up in your home.

So I ask all caregivers — DD, mental health, and adult family care (AFC) — do you know what autism spectrum disorder looks like? Should your troublesome resident belong on the autism spectrum? If not now, could it happen with a future resident? Of course it’s possible. Therefore, here is what I think you should do.

Look for the signs. Foster care providers are great monitors of their residents. You are where the rubber meets the road, medically speaking. You’ll catch things way before anyone else does. You don’t have to diagnosis, you just have to suspect.

Look for the signs. Foster care providers are great monitors of their residents. You are where the rubber meets the road, medically speaking. You’ll catch things way before anyone else does. You don’t have to diagnosis, you just have to suspect.

When in doubt, call it out. Document your observations and get them to the doctor and ask the question — “Is this autism?”

If it is autism, adjust your caregiving. Autism is a disorder of social interaction and communication. They can’t react as other residents do. You will have to help them compensate for their disability. When you do, things should go that much more smoothly in your home.

Now let’s look at the other side of the coin. If you have a diagnosis of autism and therapy is not working, is it really autism that you’re dealing with? Since there are no definitive tests, there is always an element of guessing going on. What if they guessed wrong? There are several conditions that look like some aspects of autism spectrum disorder.

They are:

- Hearing loss

- Psychological disorders

- Avoidant personality disorder

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Reactive attachment disorder

- Social (pragmatic) communication disorder

- Schizophrenia, which rarely happens in children

- Lead poisoning

- Genetic disorders

- Down syndrome

- Tuberous sclerosis

Here again the caregiver steps are “look for the signs” and “when in doubt, call it out.”

Medication Management

Now that we know the possibility is real, let’s talk about caregiver tools and techniques in regard to ASD. Since I’m a pharmacist, I’ll start off with the drugs that may be used in treatment and what you might have to do with them.

Medication therapy is seen in up to 62 percent of cases. Medications are used to help control behaviors that make it difficult for the patient to integrate into home, school, and work environments. In my experience, that percentage starts out higher in care homes. New residents to your home typically bring with them a mixed bag of pills. I have found that unskilled family caregivers and other well-meaning support personnel sometimes use medications as a chemical babysitter or restraint. The result is the target behavior is controlled but the side effects are not managed well, which usually results in more medications to control the side effects. When the resident gets established in a stable and professional foster care home, the need for medications usually diminishes. Care providers should carefully review the med list periodically to see if the drug is still needed. And as always, be familiar with what side effects can occur. They might be more of an issue than the original problem.

Here’s a table of some common meds used in ASD. Though some of these medications will be familiar to caregivers, their intended effect may be different than what you are used to. The side effects that may appear may also be different than what you have typically seen in your other residents.

Drug Type Treats Side Effects

|

Stimulants methylphenidate (Ritalin, Metadate, Concerta, Methylin, Focalin, Daytrana) mixed amphetamine salts (Adderall) dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine) lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) |

Hyperactivity Short attention span Impulsive behaviors |

Common Problems falling asleep Low appetite Irritability Emotional outbursts |

Less Common Anxiety Depression Repeating behaviors and thoughts Headaches Diarrhea Social withdrawal Changes in heart rate Tics |

|

Alpha Agonist guanfacine (Tenex, Intuniv) clonidine (Catapres, Kapvay) |

Hyperactivity Short attention span Impulsive behaviors Sleep problems Tics |

Sleepiness Irritability |

Aggression Low appetite Low blood pressure Constipation |

|

Antidepressant fluoxetine (Prozac) fluvoxamine (Luvox) sertraline (Zoloft) paroxetine (Paxil) citalopram (Celexa) escitalopram (Lexapro) |

Depression Anxiety Repeating thoughts Repeating behaviors |

GI problems (nausea, vomiting, constipation, low appetite) Headaches Problems falling asleep Sleepiness Agitation Weight gain |

Seizure Thoughts of harming self Suicide Serotonin syndrome |

|

Antipsychotics risperdone (Risperdal) olanzapine (Zyprexa) quetiapine (Seroquel) aripiprazole (Abilify) ziprasidone (Geodon) |

Irritability Aggression Self-injury Tantrums Sleep problems High activity level Repeating behaviors Tics |

Sleepiness Drooling Increased appetite and weight gain |

High blood sugar, diabetes High cholesterol Tardive dyskinesia (abnormal movements) Quetiapine – eye side effects Ziprasidone – heart side effects |

|

Anti-Seizures/Mood Stabilizers carbamazepine (Tegretol, Carbatrol) valproic acid (Depakote, Depakene) lamotrigine (Lamictal) oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) topiramate (Topamax) clonazepam (Klonopin) alprazolam (Xanax) |

Seizures Mood problems Aggression Self-injury Anxiety

|

Sleepiness Nausea Vomiting Confusion Clonazepam and Alprazolam –impaired memory, judgement, and coordination |

Dizziness Rashes Memory problems Hepatitis Liver failure Pancreatitis Bone marrow suppression Tremor Depression Clonazepam and Alprazolam – Paranoia Valproic acid – fever, hair loss

|

Behavioral Management

Because autism is a spectrum of disorders, each person will have their own unique set of strengths and weaknesses that influences how they have developed. By the time they arrive at your care home they will inevitably have acquired some maladaptive behaviors that need to be addressed. As you start working with your autistic resident, care providers must remember that there will be unique communication problems and a lack of social understanding. That doesn’t mean that they will be problem residents, it just means that caregivers will have to adapt their techniques to get the desired results.

- Accept your resident, quirks and all. Don’t fall into the trap of comparing the autistic patient with “normal” people (if there is such a thing). It helps to remember that there is a developmental handicap and the person can’t act “normally.” That doesn’t mean they can’t fit in given the right support.

- Don’t give up. Your resident will adapt but at their own pace, dictated by their weaknesses and strengths. Work around what is missing and learn to enjoy the strengths.

- Become an expert on your resident. Figure out what triggers a behavior. Find out what is stressful and challenging. Discover what is calming and enjoyable. Record your discoveries in your files so you can educate others more easily.

- Become the resident’s advocate with the world. Educate others about the limitations and quirks that you have discovered. Help the resident communicate with those he or she will come in contact with.

- Learn about autism. You’re not in this alone. There is a wealth of information on ASD that others have discovered that you can take advantage of. I will provide starting points for your research later on.

Helping Your Child with Autism Thrive: Tips from the Help Guide at Autism Speaks

Tip 1: Provide structure and safety.

- Be consistent. Children with ASD have a hard time applying what they’ve learned in one setting (such as the therapist’s office or school) to others, including the home. For example, your child may use sign language at school to communicate, but never think to do so at home. Creating consistency in your child’s environment is the best way to reinforce learning. Find out what your child’s therapists are doing and continue their techniques at home. Explore the possibility of having therapy take place in more than one place in order to encourage your child to transfer what he or she has learned from one environment to another. It’s also important to be consistent in the way you interact with your child and deal with challenging behaviors.

- Stick to a schedule. Children with ASD tend to do best when they have a highly structured schedule or routine. Again, this goes back to the consistency they both need and crave. Set up a schedule for your child, with regular times for meals, therapy, school, and bedtime. Try to keep disruptions to this routine to a minimum. If there is an unavoidable schedule change, prepare your child for it in advance.

- Reward good behavior. Positive reinforcement can go a long way with children with ASD, so make an effort to “catch them doing something good.” Praise them when they act appropriately or learn a new skill, being very specific about what behavior they’re being praised for. Also look for other ways to reward them for good behavior, such as giving them a sticker or letting them play with a favorite toy.

- Create a home safety zone. Carve out a private space in your home where your child can relax, feel secure, and be safe. This will involve organizing and setting boundaries in ways your child can understand. Visual cues can be helpful (e.g., colored tape marking areas that are off-limits, labeling items in the house with pictures). You may also need to safety-proof the house, particularly if your child is prone to tantrums or other self-injurious behaviors.

Tip 2: Find nonverbal ways to connect.

- Connecting with a child with ASD can be challenging, but you don’t need to talk — or even touch — in order to communicate and bond. You communicate by the way you look at your child, by the tone of your voice, your body language, and possibly the way you touch your child. Your child is also communicating with you, even if he or she never speaks. You just need to learn the language.

- Look for nonverbal cues. If you are observant and aware, you can learn to pick up on the nonverbal cues that children with ASD use to communicate. Pay attention to the kinds of sounds they make, their facial expressions, and the gestures they use when they’re tired, hungry, or want something.

- Figure out the motivation behind the tantrum. It’s only natural to feel upset when you are misunderstood or ignored, and it’s no different for children with ASD. When children with ASD act out, it’s often because you’re not picking up on their nonverbal cues. Throwing a tantrum is their way of communicating their frustration and getting your attention.

- Make time for fun. A child coping with ASD is still a child. For both children with ASD and their parents, there needs to be more to life than therapy. Schedule playtime when your child is most alert and awake. Figure out ways to have fun together by thinking about the things that make your child smile, laugh, and come out of her/his shell. Your child is likely to enjoy these activities most if they don’t seem therapeutic or educational. There are tremendous benefits that result from your enjoyment of your child’s company and from your child’s enjoyment of spending unpressured time with you. Play is an essential part of learning for all children and shouldn’t feel like work.

- Pay attention to your child’s sensory sensitivities. Many children with ASD are hypersensitive to light, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Some children with autism are “under-sensitive” to sensory stimuli. Figure out what sights, sounds, smells, movements, and tactile sensations trigger your kid’s “bad” or disruptive behaviors and what elicits a positive response. What does your child find stressful? Calming? Uncomfortable? Enjoyable? If you understand what affects your child, you’ll be better at troubleshooting problems, preventing situations that cause difficulties, and creating successful experiences.

Source https://www.helpguide.org/articles/autism-learning-disabilities/helping-your-child-with-autism-thrive.htm

Developmental Management

Autistic residents may be developmentally handicapped, but they can learn to adapt and grow if given the right support. The doctor and the autism specialist team may develop a long-term care plan. You may hear different or even conflicting recommendations from parents, teachers, and doctors. Be the resident’s advocate and straighten things out. Keep in mind that there is no single treatment that works for everyone. Be the doctor’s eyes and ears and report back how therapy is going.

- Help, but not too much. Development will be slowed if the resident is coddled too much. Help develop the life skills that will serve the resident throughout their life.

- Learn more about autism home-based and school-based treatments and interventions for autism.

- Play and interact with the children in ways that promote social interaction skills, manage problem behaviors, and teach daily living skills and communication.

- Take advantage of programs and specialists that are all around you.

Autism Resource Research Starting Points

Autism Navigator: https://autismnavigator.com/

Autism Speaks: https://www.autismspeaks.org

https://www.autismspeaks.org/tool-kit

Autism Society: https://www.autism-society.org/

https://www.autism-society.org/about-the-autism-society/contact-us/

To speak to an I&R Specialist directly, call 800-3-AUTISM (800-328-8476).

Autism Today: https://autismtoday.com/

CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/index.html

Conclusion

The perception of autism has changed from separate individual disorders to viewing them as a whole spectrum of the same disorder. This has shifted the emphasis from diagnosis to therapy selection and patient development. Though diagnosis could take a team of experts and years to complete, the needs of the patient can start to be fulfilled right away.

With this change comes the possibility of missed diagnosis in current residents of any type of care home. With this realization, difficult patients may belong on the autism spectrum. Caregivers must look for the signs and bring their observations to the doctor’s attention. Once a patient is diagnosed, elements of regular home living can become therapy. Because of communication and social interaction disabilities, the caregiver will need to adjust their caregiving to meet the needs of the autistic resident. This CE is just the beginning. The need for further education is self-evident.

Good luck in your ASD caregiving,

Mark Parkinson, BS Pharm

References:

Autism Spectrum Disorder. National Institute of Mental Health, NIH. 2019. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/autism-spectrum-disorders-asd/index.shtml

Autism spectrum disorder. MayoClinic, 2019. Jan. 06, 2018. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352928

Autism Spectrum Disorders. HelpGuide 2019. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/autism-learning-disabilities/autism-spectrum-disorders.htm

Helping Your Child with Autism Thrive. HelpGuide 2019. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/autism-learning-disabilities/helping-your-child-with-autism-thrive.htm

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Aug. 27 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html

Practical Oral care for People with Autism. NIH Publication No. 09–5190 July 2009. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/practical-oral-care-autism.pdf

Narek Israelyana, Kara Gross Margolisb, Serotonin as a Link Between the Gut-Brain-Microbiome Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2018 Jun; 132: 1–6. NBCI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6368356/

Autism. National Center for Complementary and Integrated Health NIH. Sep.24, 2017 . https://nccih.nih.gov/health/autism

What Drugs Are Used for Treating Autism? Applied Behavior Analysis Edu.Org 2019. https://www.appliedbehavioranalysisedu.org/what-drugs-are-used-for-treating autism/#targetText=Anticonvulsants%20are%20among%20the%20few,third%20of%20autism%20patients%20do.

Tool Kit. AutismSpeaks. 2019. https://www.autismspeaks.org/tool-kit

Exam Portal

click on [Take Exam]

Purchase membership here to unlock Exam Portal.

|

|

|

|

|

*Important*

Registration and login is required to place your name on your CE Certificates and access your certificate history.

Username MUST be how you want your name on your CE Certificate.

| Guest: Purchase Exam |