LATE Dementia, the Alzheimer Mimic

LATE Dementia, the Alzheimer Mimic

Author: Mark Parkinson BsPharm: President AFC-CE

Credit Hours 1- Approximate time required: 60 min.

Educational Goal

Educate caregivers about a newly describe form of dementia Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy. (LATE)

Educational Objectives

Provide variety in dementia training.

Describe LATE dementia

Tell how the discovery of LATE dementia effects medical research

Provide caregiver techniques in regard to residents who show signs of dementia.

Procedure:

Read the course materials. 2. Click on exam portal [Take Exam]. 3. If you have not done so yet fill in Register form (username must be the name you want on your CE certificate). 4. Log in 5. Take exam. 6. Click on [Show Results] when done and follow the instructions that appear. 7. A score of 70% or better is considered passing and a Certificate of Completion will be generated for your records.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. All procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this article should not be used by care providers without evaluation of their patients’ Doctor. Some conditions and possible contraindications may be of concern. All applicable manufacturers’ product information should be reviewed before use. The author and publisher of this continuing education program have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that all information contained herein is accurate in accordance with the latest available scientific knowledge at the time of acceptance for publication. Nutritional products discussed are not intended for the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of any disease.

LATE Dementia, the Alzheimer Mimic

LATE Dementia Alzheimer's Disease

Something New in Dementia

Continuing education courses about dementia are constants in the adult foster care industry. You all have read the same concepts over and over again. This time, though, the dementia training will be different. Something new has come up that is the cutting edge of medical science. For now, it’s called limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, or LATE Dementia. The reason it warrants a CE course of its own for caregivers is that it looks and acts just like Alzheimer’s disease. Its discovery is impacting Alzheimer’s research and may have an impact on future Alzheimer’s therapy. Besides that, it’s about time you had some variety in dementia-related courses.

An article about LATE dementia was published this year in Oxford Academic’s Brain journal. The news is spreading quickly, and the medical science community’s reaction to it gives an interesting insight into how medical research is done. The article was the result of an international consensus of researchers from Britain’s Rush University Medical Center and scientists from several National Institutes of Health-funded institutions in the United States. For the advanced science geeks among you, the full article can be read for free at the following link: https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/142/6/1503/5481202

Fair warning, though, it’s pretty advanced reading (kind of refreshing in a weird way for the advanced medical professional). For the rest of us non-science geeks I will cover the details here and talk about its implications in more everyday language.

Alzheimer’s Disease Symptoms

As you know, Alzheimer’s is a difficult-to-diagnose disease that is predominantly recognized by the dementia symptoms of:

- Increased memory loss and confusion

- Inability to learn new things

- Difficulty with language and problems with reading, writing, and working with numbers

- Difficulty organizing thoughts and thinking logically

- Shortened attention span

- Problems coping with new situations

- Difficulty carrying out multistep tasks, such as getting dressed

- Problems recognizing family and friends

- Hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia

- Impulsive behavior such as undressing at inappropriate times or places, or using vulgar language

- Inappropriate outbursts of anger

- Restlessness, agitation, anxiety, tearfulness, or wandering—especially in the late afternoon or evening

- Repetitive statements or movements and occasional muscle twitches

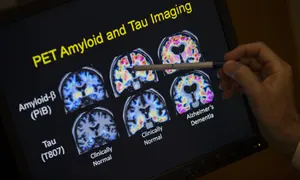

These signs of Alzheimer’s disease may be caused by the loss of brain matter due to changes in certain proteins in the brain. It is thought that the buildup of tau protein tangles and plaques of beta-amyloids (leftover fragment of larger proteins) interfere with the brain tissue’s normal functions and the brain cells die. The loss of brain cells leads to loss of brain function, causing the dementia symptoms.

You may have noticed I used the phrases “may be” and “it is thought.” There is a large amount of uncertainty in what is happening in the brain of dementia patients. There are many cases where dementia symptoms have occurred and there is no buildup of tau tangles and beta-amyloid plaques. These cases have baffled Alzheimer’s researchers, leading them to search for other possible causes of dementia. After months and years of study, another cause of dementia symptoms has been identified and named: deposits of a misfolded protein called TDP-43 in the brain.

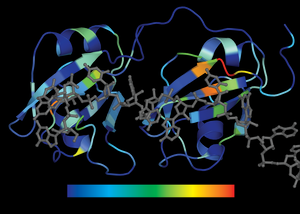

TDP-43 Error and the Cause of Disease

The transactive response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa, or TDP-43 for short, is a protein that helps regulate gene expressions of DNA and RNA. Think of it as a chemical tool the brain cell uses in getting its work done in the nucleus. TDP-43 is a highly folded molecule that attaches to DNA and RNA in specific ways in order for it to work properly.

Unfortunately, a mutation can and does occur in a cell’s DNA and a misfolded TDP-43 is created. The misfolding error changes the protein’s shape. The change in shape interferes with the protein’s proper function. As the misfolded TDP-43 accumulates in the brain, malfunctions start to occur, resulting in memory loss and thinking skill problems. Misfolded TDP-43 malfunction is also a factor in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

Recent brain tissue studies have found that misfolded TDP-43 protein is very common in older adults — about one-quarter of people over 85 have enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect activities of daily living. In my opinion, this may partially explain the aging process of the brain.

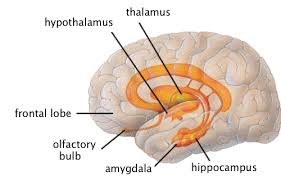

LATE Dementia

Misfolded TDP-43 is a major factor in LATE-caused dementia. As the malfunctioning protein starts to accumulate, protein tangles start to appear outside of the nucleus. When tangles accumulate in the cells of limbic regions of the brain, dementia symptoms start to occur. The limbic system of the brain is heavily involved in memory recall and memory storage, emotions, and survival instincts. As damage in the limbic regions increases, so does memory loss. Emotions such as fear and anger become harder to manage. Changes in personality are seen and the ability to think clearly decreases. These are all classic signs of dementia.

LATE dementia progresses in three phases.

- Stage 1 – TDP-43 accumulates in the amygdala.

- Stage 2 – TDP tangles spreads to the hippocampus.

- Stage 3 –TDP tangles have started to accumulate in the middle frontal gyrus of the frontal lobe of the brain.

So far, research shows that the onset of LATE dementia occurs later in life. In brain autopsies, the condition is seen in “the oldest of the old.” The reason for the age relationship was not discussed in the articles I researched. I speculate that it is part of the age-related breakdown of the repair mechanisms of the brain. If the breakdown occurs in the limbic system, you get dementia. That is just a guess on my part, though.

Another limitation I found in the articles I read was that currently the only way to make a certain diagnosis of LATE dementia is through a brain autopsy. Also, there is no cure or even a way to slow LATE dementia down. Not very useful for living patients with dementia symptoms. Clearly, more work needs to be done. But medical science has to start somewhere, and the discovery of LATE dementia is still very significant. It gives hope that other discoveries may lead to other advances in understanding dementia, and maybe one day we’ll find a remedy for it.

Caregivers and LATE Dementia

So, if you can’t detect LATE dementia without a brain autopsy (that’s not going to happen very often) and you can’t cure it, why bother writing a course about it? What good does knowing all this do for caregivers? Good questions. Kind of cynical thinking, but valid reasoning nonetheless.

There are a couple of reasons I wrote this course. I thought that you would like a break from the standard dementia course. Don’t you get tired of reading the same thing over and over again? Also, you have to admit, learning something brand-new and interesting in your chosen career field is kind of cool. But beyond the entertainment value, there are practical applications for caregivers in knowing about another cause of dementia.

There are a couple of reasons I wrote this course. I thought that you would like a break from the standard dementia course. Don’t you get tired of reading the same thing over and over again? Also, you have to admit, learning something brand-new and interesting in your chosen career field is kind of cool. But beyond the entertainment value, there are practical applications for caregivers in knowing about another cause of dementia.

Firstly, I have always considered adult foster care providers as medical professionals. You are not just babysitters but valuable members of the medical caregiving spectrum. In order for you to interact effectively with other members of the medical community, you have to be up-to-date with your understanding of medicine. Also, you are the first point of contact with the patient and their family. If they hear of LATE dementia, they will understandably have questions and hopes for new therapeutic options. You can provide those answers and help them to have realistic expectations. Dashed hopes only leads to depression and anger. Besides, it’s just good business sense to be more knowledgeable than your competition.

Late Dementia Versus Alzheimer’s Disease

Medically speaking, the discovery of LATE is very significant across all causes of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. It has filled in gaps in our understanding and changed the way we perceive dementia. We now know that LATE mimics Alzheimer’s-caused dementia so closely that we didn’t even know it was there. The only visible difference between the two is that LATE occurs primarily in adults over 80 years old. Autopsy studies show that between 20 to 50 percent of people in this age group have signs of TDP-43 tangles. In contrast, the first signs of Alzheimer’s start to manifest themselves decades earlier. Other than the age thing, it’s almost impossible to tell the difference between LATE and Alzheimer’s in live patients.

Because of this fact, researchers are starting to wonder if what was once diagnosed as Alzheimer’s was actually LATE instead. It has been estimated that 15 to 20 percent of Alzheimer’s cases should actually have been diagnosed as LATE. To complicate things even further, they have found several cases where both Alzheimer’s and LATE pathology caused the dementia symptoms.

So why should we even care? Dementia is dementia, after all. Calling it LATE or Alzheimer’s doesn’t really affect how we care for the patient. In caregiving, that’s true, but in medical research the possibility that cases were mislabeled changes everything. All the conclusions drawn from all previous studies could now be wrong. It’s like we have to start all over again in many ways.

For example, consider a drug trial that targets the Alzheimer’s disease process. They give the drug to a thousand dementia patients and the results are disappointing. It worked for some patients but had no effect on others. The researchers then concluded that the drug doesn’t work for enough Alzheimer’s patients, so they went in a different direction.

Suppose now that those non-responders didn’t have Alzheimer’s at all but had LATE instead? The conclusion that the drug didn’t work was actually wrong. It did work; the poor responses were a result of giving the drug to the wrong type of patient. You can’t treat a disease that wasn’t there in the first place.

Going forward, dementia research now has to take LATE into consideration. Old projects could be reevaluated. Abandoned lines of thought could be resurrected. The challenge now is determining who has LATE dementia and who has Alzheimer’s dementia so that proper studies can be done. The race is on now to find biological markers for LATE that doesn’t involve cutting out a portion of a living brain and putting it under a microscope.

LATE Therapy

I know that information that the caregiver can use in their work is kind of skinny in this article, so let’s put some meat on the bone for you to chew on.

Brain cell damage due to LATE is irreversible. You can’t regrow brain tissue that has been lost. That leaves utilizing what brain function remains in the best way possible. The overriding caregiving principle is that YOU have to change and adapt because the resident can’t. The disease has robbed them of the mental capacities they once had.

Here are some caregiver tips, ideas and tools that will help.

- Create a reliable daily routine with small rituals (less change to cope with).

- Allow for unusual behavior. Reduce your rejection of bizarre behavior unless it endangers someone.

- Keep the lines of communication open with family, friends, and loved ones. Educate them so there is less social rejection.

- Keep the home well-lit using soft natural light. Avoid fluorescent lights, which can agitate people with dementia.

- Demonstrate what you want the patient to do (takes less brain power to understand).

- Lay out the clothes in the right sequence (less decision-making needed).

- Clearly mark the toilet, e.g., a colorful door with a symbol (visual cue again. You can do the same with other activities of daily living tasks).

- Make going to the toilet part of the daily routine.

- The inside of the toilet bowl should be dark (e.g., by coloring the water). A totally white toilet does not allow orientation, especially for men while urinating in a standing position.

- Restlessness sometimes indicates a need to go to the toilet.

- Control napping to avoid sundowners.

- Speak slowly, not too loud, using a low-pitched voice.

- Face the person when you are speaking to them.

- Use short, familiar words and short, simple sentences that clearly express what you want to say.

- Allow sufficient time to respond. If the person does not respond, repeat your question with the same wording as before.

- Ask only one question or give one instruction at a time. Break tasks down into smaller steps that are more manageable. For instance, even activities as simple as tooth brushing are made up of many smaller tasks, such as picking up the toothpaste, taking off the cap, picking up the toothbrush, putting toothpaste on the brush, etc.

- Don’t confront … redirect instead. Avoid saying "don't" or giving negative commands. For example, instead of saying "Don't go in that room," try saying "Let's go over here."

- Avoid questions that require a lot of thought, memory, and words.

- Avoid instructions that require the patient to remember more than one action at a time (for example, avoid questions of the type "What film did you see last night?" or "What did you do this morning?").

- Avoid arguing or disagreeing with the patient. Since dementia affects reason and logic, and arguing with someone requires logic, arguing is pointless.

- Address the feelings of a person with dementia rather than focusing on the facts or accuracy of what the person is saying. Avoid reorienting the person to reality if not necessary. For instance, if someone with dementia thinks that the year is 1970, and this is not hurting anyone, refrain from trying to convince them it’s not. Instead, try to identify feelings related to 1970 by asking more about it.

- Keep things peaceful and simple.

Thanks to Dementia.com for most of these tips. For even more, visit their website at https://www.dementia.com/coping-with.html.

Conclusion

The neurodegenerative syndrome that is dementia can be caused by a number of different factors. Despite the popular belief, not all dementia is caused by Alzheimer’s disease. The discovery of LATE is filling in many gaps in our understanding of the condition. The challenge now for researchers is to find ways of identifying cases in live patients so that studies can be more accurate and effective. For caregivers, the challenge is to understand LATE and communicate with other medical professionals, residents, and their families effectively. Caregiving in dementia is about adapting to the client’s reducing mental capacities.

I hope you enjoyed the article and got some benefit out of it.

As always, good luck in your caregiving efforts.

Mark Parkinson, BSPharm

References:

TDP-43. Alzpedia Alzforum. 2019. https://www.alzforum.org/alzpedia/tdp-43

Peter T Nelson et al. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE): consensus working group report. Brain. Volume 142, Issue 6 June 2019. https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/142/6/1503/5481202

Researchers define Alzheimer's-like brain disorder. Science Daily. Apr.30 2019. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/04/190430121800.htm

We Totally Missed a Different Kind of Dementia for Decades. SciSchow Psych. Sep. 26 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CC2LG5TQn_4

Scientists Identify New Type of Dementia That Mimics Alzheimer’s. Being Patient. May 1 2019 https://www.beingpatient.com/late-dementia/

Coping with dementia. Dementia.com. 2019. https://www.dementia.com/coping-with.html

Exam Portal

click on [Take Exam]

Purchase membership here to unlock Exam Portal.

|

|

|

|

|

*Important*

Registration and login is required to place your name on your CE Certificates and access your certificate history.

Username MUST be how you want your name on your CE Certificate.

| Guest: Purchase Exam |