A Gut Reaction:

An overview of the gastrointestinal system and what can go wrong with it

Author: Mark Parkinson BsParm: President AFC-CE

Credit Hours 4- Approximate time required: 240 min.

Educational Goal:

Provide a great understanding of the gastrointestinal tract and it’s associated disorders.

Educational Objectives:

Describe the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract.

Explain how physiology gastrointestinal tract works.

List and provide an overview of GI specific disorders.

Provide caregiver principles that manage GI symptoms

Procedure:

Read the course materials. 2. Click on exam portal [Take Exam]. 3. If you have not done so yet fill in Register form (username must be the name you want on your CE certificate). 4. Log in 5. Take exam. 6. Click on [Show Results] when done and follow the instructions that appear. 7. A score of 70% or better is considered passing and a Certificate of Completion will be generated for your records.

Disclaimer

The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. All procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this article should not be used by care providers without evaluation of their patients’ Doctor. Some conditions and possible contraindications may be of concern. All applicable manufacturers’ product information should be reviewed before use. The author and publisher of this continuing education program have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that all information contained herein is accurate in accordance with the latest available scientific knowledge at the time of acceptance for publication. Nutritional products discussed are not intended for the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of any disease.

A Gut Reaction:

An overview of the gastrointestinal system and what can go wrong with it

Sometimes I think the human body is very strange and frustrating for caregivers. Isn’t it a mystery how the same food served to different residents has such varying effect? The food that makes one resident happy and content gives the other resident gas and diarrhea. Isn’t it strange how a resident can, just out of the blue, develop stomach pains and complain of constipation and bloating? Isn’t it worrisome when those symptoms turn into long-term problems? How is a caregiver supposed to react? Do you just change the menu? Do you start looking for possible health problems? Which diseases do you look for?

|

Have you ever noticed how many diseases have the same gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms? A resident who complains of chronic nausea, gas, stomachache, diarrhea, or constipation (or both) might be suffering from Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), lactose intolerance, several different cancers, ulcerative colitis (UC) or simple food allergies. I ask you, how’s a caregiver supposed to keep it all straight? Does that resident who complains of chronic irritable bowels have a food allergy or colitis or IBS or, heaven forbid, cancer? How can different diseases have the exact same symptoms, for goodness’ sake? More importantly, how is a caregiver supposed to cook for and take care of the resident with chronic stomach complaints?

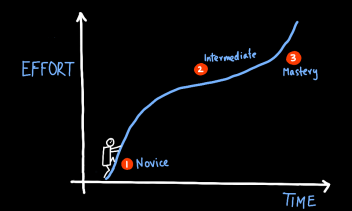

What you need is more knowledge about the digestive system. As a medical professional, you need to be a little higher on the learning curve than other people. As a foster care provider that manages a resident’s diet, you need more training on how food affects your clientele. Let’s work on those things. It’s my “gut reaction” that you will receive some useful information that will help you in your caregiving when something goes wrong in the gut.

Structure (Anatomy)

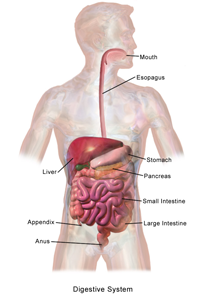

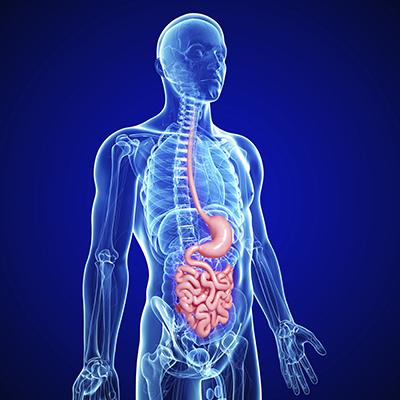

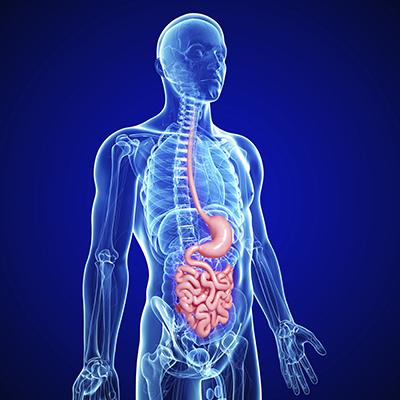

The Gut

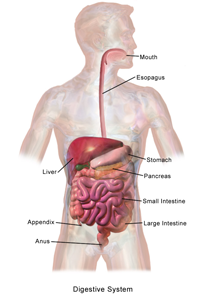

To understand what’s going wrong, you first have to understand what’s going on. Let’s go over the basic anatomy and physiology of your inner parts. Your gut is essentially a long tube that passes through your body from your mouth to your bottom, with a bunch of other organs that feed into it. It has been called the digestive system, the gastrointestinal tract, the GI tract, and the alimentary canal. It is used to take in food and liquids, break them down, absorb the useable material, and then excrete what’s left over.

|

Interesting fact

Medically speaking, the inside of the gut is considered to be outside of the body. That explains why it take a while for medication to start working: It has to be absorbed first. The drug is not really in the body until after it makes it through the lining of the gut.

|

At any given time, there are tens of thousands of different reactions occurring all along the GI tract. That’s way too many to comprehend all at once, so let’s break the gut down into more easily understandable parts.

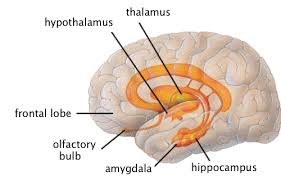

The gastrointestinal tract is a series of tubes closed off from each other by various structures. The GI tract consists of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus. Add to that the salivary glands, liver, pancreases, gallbladder, blood vessels, nerves and hormones, and you get the digestive system. The gastrointestinal tract is also commonly divided into the upper GI tract (the mouth to just past the stomach) and the lower GI tract (most of the small intestine to the anus). The entire digestive system is wrapped up and held in place by a membranous sac called the peritoneum.

Histology (Gastrointestinal Tissues)

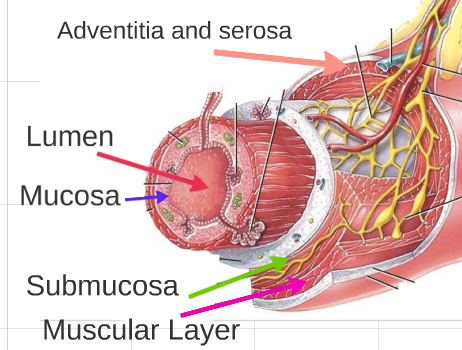

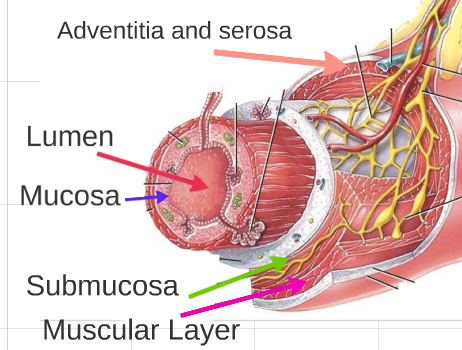

The tissues that make up the GI tract are made up of four different layers: the mucosa, submucosa, muscular layer and adventitia or serosa. Each section of the GI tract has additional specialized cells that aid in the digestion process.

Lumen

The lumen is not a tissue; rather, it’s the hollow part at the center of any tube. It’s the canal that the food travels down.

Mucosa

The mucosa is the innermost layer, the part that comes in contact with the food. It’s where most of the digestive action takes place. It’s packed with specialized cells that perform the necessary functions of the different areas of the alimentary canal.

The mucosa itself has three layers:

- The epithelium, which contains the cells that excrete, absorb, and digest.

- The lamina propria, which is mainly connective tissue.

- The muscularis mucosae, a thin layer of smooth muscles that helps move the food around.

Submucosa

The submucosa is the next layer out. It mainly contains dense connective tissue that houses large blood vessels, nerves, and lymph vessels.

Muscular Layer

The muscular layer is made up of two levels of muscle tissue laid down in two separate ways. The inner layer wraps around in a circular manner. It prevents the food from traveling backwards. The outer layer is laid out lengthwise. When the muscles contract, they move the food forward. Between the muscle layers lies the myenteric plexus. It is the part of the nervous system that controls the muscles. Think of it as the pacemaker of the gut; it starts the rhythmic contraction called peristalsis.

Peristalsis is the wave of muscular contractions that run the length of the alimentary canal. It involves all three layers of muscle of the gut, including the thin muscle layer in the mucosa.

|

Interesting Fact

Peristalsis occurs at different rates in different parts of the GI tract — roughly three contractions per minute in the stomach, 12 per minute in the duodenum, nine per minute in the ileum, and one per 30 minutes in the large intestines. Of course, the presence of different kinds of foods affects the rate of contraction. More about peristalsis later.

|

Adventitia and serosa

The outermost layer of the GI tract has several layers of connective tissues that include the adventitia and serosa. I know that was a lot to take in. Don’t worry, though; it will all start to come together for you as we talk about the function of the gut’s different parts.

Function (Physiology)

To help you understand the functioning of the digestive system I want you to stop reading and go grab a snack. Get something substantial and delicious. Go ahead, I’ll wait…. (If the snack involves chocolate, bring enough for me too.) Got it? Good. Take a big bite.

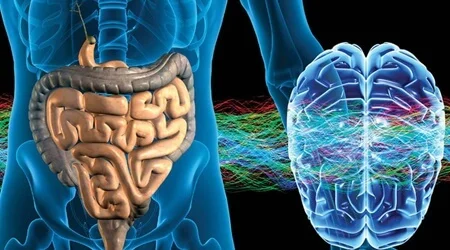

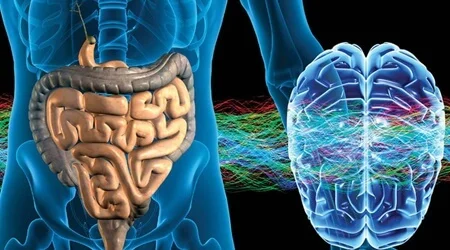

We’re going to follow that bite down the digestive tract. The first step in that journey starts in an unusual place: the brain.

Cephalic Phase of Digestion

There is a two-way communication connection between the gut and the brain called the gut-brain axis. It involves hormones and the autonomous nervous system (the nervous system that operates without much conscious thought). When you think about food, the brain automatically sends signals to the digestive system to get ramped up. It says, “Get ready, food’s coming.” The salivary glands start to produce saliva, peristalsis increases, and other systems are stimulated. Oh, by the way, in case you haven’t guessed it already, cephalic means pertaining to the brain.

The Mouth

After you take your first bite of food, the chewing process starts to break down the food and mixes it with saliva. The saliva moistens the food and turns it into an easily transportable soft mass called a bolus. Enzymes in the saliva start to chemically break down the bolus. Sensory signals are sent back to the brain and your brain decides if it likes or dislikes the food you’re chewing.

|

Interesting Fact

You have three pairs of salivary glands and they normally produce about two pints of liquid a day.

|

Esophagus

If your brain decides it likes or at least tolerates the snack you have chosen to eat, you swallow the bolus and it travels down the esophagus. As the bolus bulges into the esophagus, stretch receptors trigger a peristaltic reaction. Muscles relax in front of the bolus and contract around the bolus, propelling the food toward the stomach.

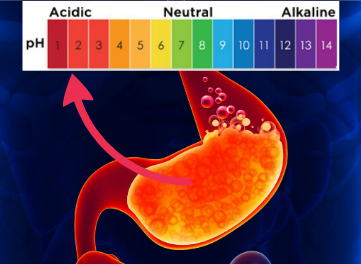

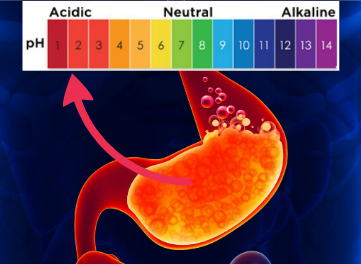

Stomach

Your snack bolus enters the stomach when the peristaltic wave relaxes the muscles of the esophageal sphincter. A sphincter is a band of muscles that closes off certain parts of the GI tract. Once in the stomach, the food is churned and mixed with stomach acids, enzymes, and fluids until it has turned into a liquidy paste called chyme. The chyme is then pushed through the bottom pyloric sphincter into the small intestine about an eighth of an ounce at a time.

|

Interesting Fact

The stomach acid and enzymes are very powerful. They are just about as strong as battery acid in breaking down material. The GI tract has layer upon layer of protection so that we don’t digest our own gut.

|

Small Intestine

Your snack’s chyme enters into the small intestine where it is mixed with other digestive juices to continue the breaking-down process. It also produces chemicals that start to reduce the acidity of the chyme. The small intestine can be broken down into three sections:

- Duodenum – The duodenum is the upper part of the small intestine. It is the section where more digestive juices come from the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder.

- Jejunum – Digestion continues in the next section, called the jejunum. The nutrients from your snack start to be absorbed into your bloodstream.

- Ileum – The longest and final section, called the ileum, is where the majority of your snack’s nutrients are absorbed. Most of the stomach acid has been neutralized by this time.

Pancreas, Liver and Gallbladder

Digesting the food we eat is a very tough job. The food must be broken down to the molecular level. The pieces have to be small enough to make it through the gut lining, flow into the bloodstream, and eventually be absorbed into each individual cell. To help, the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder produce digestive chemicals and hormones that aid in the digestive process.

- Pancreas – The pancreas lays just behind the stomach and is connected to the duodenum by the pancreatic duct. Through the duct flows many of the enzymes that break down the individual components of your snack. For example, proteins and carbohydrates are still too large to be absorbed through a cell wall so enzymes chop up the molecules into smaller molecular chunks. The pancreas also produces the hormone insulin. It is delivered directly into the bloodstream. Hormones are chemicals our bodies use to control the body’s functions, including digestion, but that’s a story for another time.

- Liver – The liver lays just below the diaphragm. The liver has four main functions: 1. breaking down or converting substances in the bloodstream, 2. extracting energy from the nutrients we eat, 3. breaking down toxins so they are less harmful to the body and removing them from the bloodstream, and 4. producing bile that is stored in the gallbladder. Actually, the liver is the chemical workhorse of our body. It accomplishes over 500 different reactions. It’s where the nutrients are first sent after being absorbed into the bloodstream. In the liver, the nutrients are stored or converted into more useable molecules, like glucose.

- Gallbladder – The gallbladder is a small pouch just below the liver. It stores bile, which is used to break down the fats we eat. It empties into the duodenum at the same place as the pancreatic duct.

Large Intestine

What’s left of your snack now flows into the large intestine at a structure called the cecum. The cecum is the part that has the appendix attached to it. From the cecum, the residue flows into the colons (ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid). The large intestine’s job is to reabsorb all the useful material, leaving only a waste byproduct we call the stool.

Rectum and Anus

Once the water is removed from the stool, the stool collects in the rectum. As the rectum lining stretches, signals are sent to the brain via stretch-sensing nerve receptors. They signal the need to defecate. The anus (which is really a muscular sphincter) is told by the brain to relax and we eliminate the indigestible bits of the snack you ate hours ago.

|

Interesting Fact

The time it takes for food to pass from the mouth to your bottom is highly variable and dependent on several factors. I found this information at the Mayo Clinic’s website.

“Digestion time varies between individuals and between men and women. After you eat, it takes about six to eight hours for food to pass through your stomach and small intestine. Food then enters your large intestine (colon) for further digestion, absorption of water and, finally, elimination of undigested food.

“In the 1980s, Mayo Clinic researchers measured digestion time in 21 healthy people. Total transit time, from eating to elimination in stool, averaged 53 hours (although that figure is a little overstated, because the markers used by the researchers passed more slowly through the stomach than actual food). The average transit time through just the large intestine (colon) was 40 hours, with significant difference between men and women: 33 hours for men, 47 hours for women.”

|

Source: https://www.mayoclinic.org/digestive-system/expert-answers/faq-20058340

Nervous System

Nervous System

Remember when I told you how the brain talks to the gut via the gut-brain axis? Well, the gut talks back to the brain as well. There are over 100 million nerve cells in the digestive system. Collectively, they are called the enteric nervous system (ENS). Some medical professionals call it the body’s “second brain.” The gut also produces many hormones that chemically “talk” to the nervous system. The information superhighway between the brain and the gut is the vagal nerve. It is responsible for the majority of the nerve signals along the gut-brain axis. The gut-brain axis “nerve talk” consists of things like, “I want a snack,” “You ate too much snack,” “You ate harmful things as a snack,” “You’re allergic to the snack,” and “Boy, that snack was satisfying.”

Food is not the only thing talked about between the gut and the brain. Ever heard of a nervous stomach, or “I’m just too nervous to eat right now”? Emotions have a large effect on the gut. Warning signals also are communicated back to the brain from the gut. You can “feel/sense” when things are going wrong. We can sense inflammation, infection, dehydration, organ malfunction, and many other things. You’ve all heard of the saying, “I’ve got a gut feeling that something is wrong.”

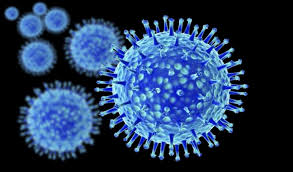

Microbiome (Bacteria)

What used to be called the gut flora is now referred to as the microbiome, for it is truly a fully functional environment all to itself. There are tens of trillions of bacteria in our gut and on our skin, with over 1,000 different known species of bacteria. Each is a chemical-producing factory. The microbiome can weigh up to 2 kilos! Functionally, the microbiome in our gut has even been referred to a digestive organ.

What used to be called the gut flora is now referred to as the microbiome, for it is truly a fully functional environment all to itself. There are tens of trillions of bacteria in our gut and on our skin, with over 1,000 different known species of bacteria. Each is a chemical-producing factory. The microbiome can weigh up to 2 kilos! Functionally, the microbiome in our gut has even been referred to a digestive organ.

- The role of bacteria in the gut – Our microbiome eats what is left over after digestion. Included in their byproducts are some important nutrients that are vital for keeping us healthy. They produce vitamin K, folate, vitamin B12, and short-chain fatty acids our intestinal cells can use as fuel. The bacteria are our first line of immunity defense. They limit and control the bad bugs and even help in breaking down some toxins. We are used to thinking of bacteria as infectious parasites, but for most of our microflora, we should think of them as our gut garden. Properly balanced, the garden helps keep us healthy. Out-of-balance gut gardens can cause problems and disease.

- Bacteria can “talk” to our brain too – New research has identified several different ways that the microbiome communicates with the brain through the enteric nervous system. They may have a larger role in influencing how we feel than was previously thought. An improperly balanced microbiome is proving to be a major factor in many disease states.

|

Interesting Fact

There are 10 times more microbiome cells than human cells in and on our body. There are also 150 times more genes in our gut garden than our own human genes.

|

Source: https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/en/about-gut-microbiota-info/

Caregiving and the Gut

You now are higher on the digestive system learning curve. You can apply this knowledge as you go about your caregiving duties. It will give you more expertise in interacting with your residents and fellow medical professionals.

You are also better primed to learn about what can go wrong in the digestive system. Already you can start to appreciate just how complex and variable the gut is. How so many factors are involved in even the most basic of GI functions. I bet you that you are even starting to think of ways to change your caregiving efforts. Let’s add even more to your understanding and medical know-how.

Gastrointestinal Pathology

Symptomatic problems can occur anywhere along the GI tract as our gut reacts to the normal variability of life events.

For example:

- Get dehydrated and the colon tries to pull more water from the stool, resulting in constipation.

- Eat something the body doesn’t like and the ENS will try to get rid of it quickly through a bout of diarrhea.

- Become too nervous and the brain overstimulates the stomach, causing a nervous stomach.

Most of the time the symptoms resolve themselves. The caregiver normally doesn’t have to be too concerned over such things. Caregiving red flags start to fly, though, when a symptom occurs over and over again or the symptoms doesn’t resolve itself and becomes a chronic issue. These are the problems that makes the caregiver start to worry. Is what you are seeing the start of something serious? We’re going to cover the disorders that occur inside the gastrointestinal tract so you can more readily answer that question.

Terminology

Gastrointestinal pathology can refer to any disorder, disease, or syndrome that occurs primarily within the GI tract. In medical terms, the words disorder, disease, and syndrome mean different things.

- Disorder – a derangement or abnormality of function; a morbid physical or mental state.

- Disease – An abnormal condition of a part, organ, or system of an organism resulting from various causes, such as infection, inflammation, environmental factors, or genetic defect, and characterized by an identifiable group of signs, symptoms, or both.

- Syndrome – A group of symptoms that collectively indicate or characterize a disease, disorder, or other condition considered abnormal. Source: The Free Dictionary by Fairfax

If you’re thinking that this still isn’t very clear, I agree. For the purpose of this course only, I will define a disorder as any abnormality of function from any cause. A disease is an abnormality that has an identifiable set of symptoms, and a syndrome is a condition or a group of symptoms where at least some of the causes are unknown.

I am going to exclude other conditions that have GI effects but originate outside the gut, like depression or Parkinson’s disease. We are also going to cover just the most common maladies. Could you imagine how long this article would be if we covered everything? It would be encyclopedia big. I just don’t have the energy to write that. So, presenting in no particular order, starting generally with the mouth and progressing toward the bottom, let’s start getting you higher on the GI pathology learning curve.

GERD

GERD stands for gastroesophageal reflux disease. It has also been called acid reflux disease. It is a condition where stomach acid backs up into the esophagus and causes damage. The esophagus does not have the same protective layers the stomach does. When the stomach acid and enzymes of the gastric juice reflux into the throat, the tissues start to break down. We feel that damage as heartburn. Other symptoms of GERD are:

- Bloating

- Bloody or black stools or bloody vomiting

- Burping

- Dysphagia — the sensation of food being stuck in your throat

- Hiccups that don't let up

- Nausea

- Weight loss for no known reason

- Wheezing, dry cough, hoarseness, or chronic sore throat

- Dry cough

If the symptoms occur more than twice week, last for hours, or occur often enough to be unusual, it might be time for a caregiver to call a doctor.

Causes

Several different factors can cause gastric juice to reflux back into the esophagus. For example, perhaps the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is damaged or obstructed, the tone of the muscle is weakened, nerves that control the muscles do not function normally, or the pressure on the stomach is too much for the sphincter. The end result is all the same — a leaky LES.

Risk Factors

Caregivers should keep a closer eye on their residents who have:

- Obesity

- Bulging of the top of the stomach up into the diaphragm (hiatal hernia)

- Pregnancy

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma

- Smoking habits

|

Interesting facts

Incidents of reported cases of GERD are increasing. Hospitalizations for GERD 1998 were 995,402. In 2005 that number climbed to 3.14 million. Between 1998 and 2005 42 percent more infants and 80 percent more children ages 2–17 were hospitalized because of GERD.

|

Source: https://www.healthline.com/health/gerd/facts-statistics-infographic#2

Gastric Disorders

Gastric means “pertaining to the stomach” and disorder means “pathological condition.” Or, in everyday terms. things are not right in the tummy.

- Gastroparesis – A condition where the stomach cannot empty itself in a normal fashion; usually muscle contraction is slowed or delayed. It is caused by nerve damage to the vagal nerve or the ENS. The nervous system is affected by uncontrolled diabetes, drugs (narcotics and antidepressants are common culprits), viral infections, and other nervous system diseases.

Symptoms include:

- Heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux (backup of stomach contents into the esophagus)

- Nausea

- Vomiting undigested food

- Early satiety (feeling full quickly when eating)

- Abdominal bloating (enlargement)

- Poor appetite and weight loss

- Poor blood sugar control

- Gastritis – Inflammation of the stomach lining. Most often from an infection. Overuse of drugs and alcohol can also inflame the stomach. Symptoms are obviously a stomachache.

- Dyspepsia – In a word, indigestion. Dyspepsia is usually just the result of bad luck, poor choices, or nerves. The savvy caregiver should not automatically write off indigestion symptoms, though, especially repeated or chronic occurrences. That is not normal and definitely could be a red-flag symptom of something worse.

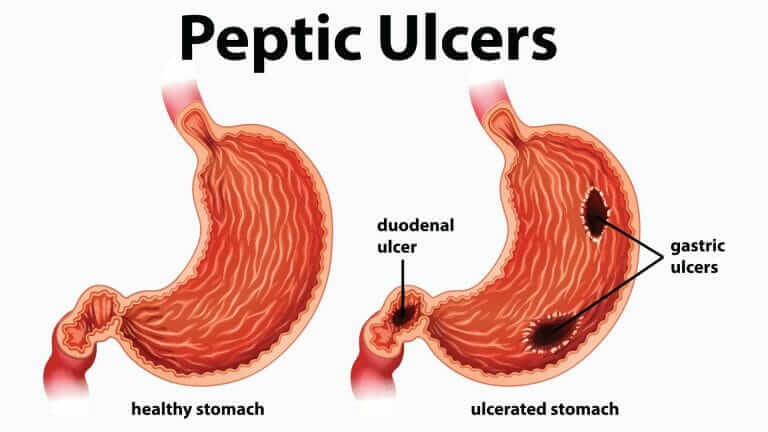

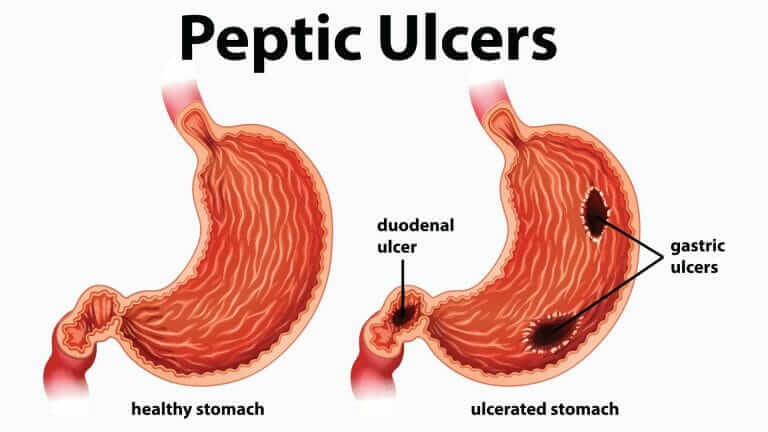

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

PUD refers to both gastric (stomach) and duodenal ulcers. An ulcer is a small hole in the protective lining of the GI tract. When gastric juices flow through the hole and come in contact with the gut tissues, damage occurs. Bleeding into the GI tract may occur.

The symptoms of an ulcer are:

- A gnawing or burning pain in the middle or upper stomach between meals or at night

- Bloating

- Heartburn

- Nausea or vomiting (the vomit may appear red or dark-colored)

Some ulcers do not cause pain, or the pain is masked by other factors. The pathology is manifested in other ways:

- Dark or black stool (due to bleeding)

- Intolerance of fatty or acidic foods or other appetite changes

- Unexplained weight loss

- An increase in anxiety or shortening of breath

- Feeling faint or lightheaded

Causes

There are three major factors that can disrupt all the protective layers of the upper GI system: Bugs, Drugs and Stress.

Bugs – Helicobacter pylori bacteria commonly live in the mucosal layer. If a colony grows abnormally large, the protective layers are disrupted and an ulcer occurs.

Drugs – The long-term use of certain drugs disrupts the production of mucus, leading to inadequate protection. NSAIDs, aspirin, SSRIs, antidepressants, Fosamax, and Actonel all list ulcers as possible side effects of continued use.

Stress – Stress can overstimulate the upper GI, which leads to an increased production of gastric juices and changes peristalsis. Eating a lot of acidic foods doesn’t help the situation, either.

Risk Factors

Smoking, alcohol, chronic stress, spicy foods, and a weakened immune system can all cause or aggravate PUD.

|

Interesting fact

A quote from an article I found.

The ENS may trigger big emotional shifts experienced by people coping with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional bowel problems such as constipation, diarrhea, bloating, pain and stomach upset. “For decades, researchers and doctors thought that anxiety and depression contributed to these problems. But our studies and others show that it may also be the other way around,” Pasricha says. Researchers are finding evidence that irritation in the gastrointestinal system may send signals to the central nervous system (CNS) that trigger mood changes. “These new findings may explain why a higher-than-normal percentage of people with IBS and functional bowel problems develop depression and anxiety.”

|

Source: John Hopkins, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/the-brain-gut-connection

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an abnormal reaction to gluten, a protein that is found in wheat, rye, and barley. When those who are genetically predisposed eat gluten, the immune system responds by attacking the lining of the small intestine. Celiac disease is not a food allergy but an abnormal autoimmune response. It can cause pain and discomfort and also lead to serious disruption of the absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The autoimmune response is variable between different patients.

Celiac disease is an abnormal reaction to gluten, a protein that is found in wheat, rye, and barley. When those who are genetically predisposed eat gluten, the immune system responds by attacking the lining of the small intestine. Celiac disease is not a food allergy but an abnormal autoimmune response. It can cause pain and discomfort and also lead to serious disruption of the absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. The autoimmune response is variable between different patients.

Causes

The exact cause is unknown. Genetics plays a role in inheriting the condition as well as infant feeding practices, bacterial infections, and microbiome imbalance.

Risk Factors

Those with a milder response may not even know they have the disease and attribute symptoms to other conditions. Caregivers, especially those who take care of developing children, should look for:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Chronic diarrhea

- Swollen belly

- Constipation

- Gas

- Pale, foul-smelling stools

- Dermatitis — the rash usually occurs on the elbows, knees, torso, scalp, or bottom

Chronic uncontrol reactions can lead to the malnutrition problems of:

- Failure to thrive for infants

- Damage to tooth enamel

- Weight loss

- Anemia

- Irritability

- Short stature

- Delayed puberty

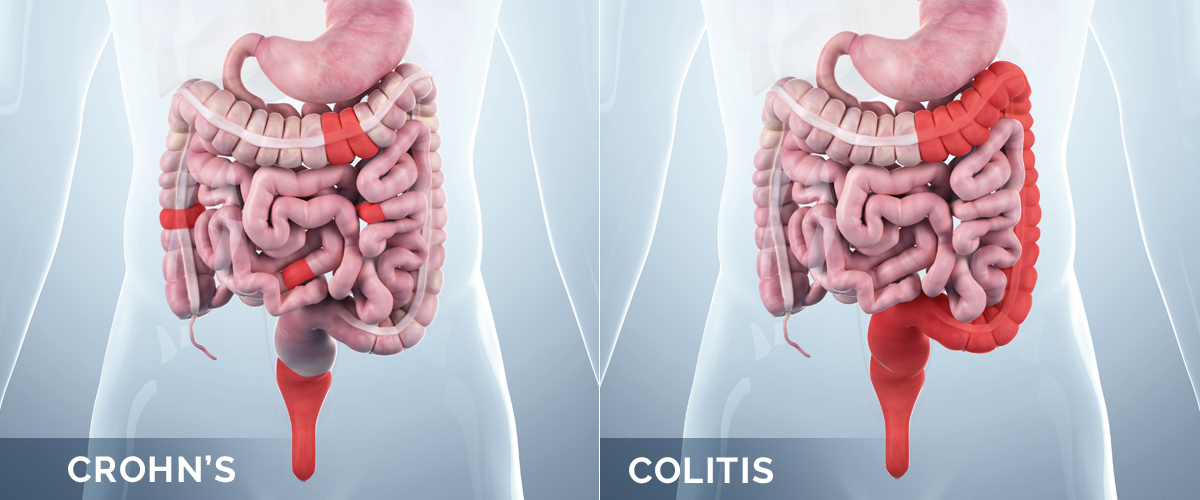

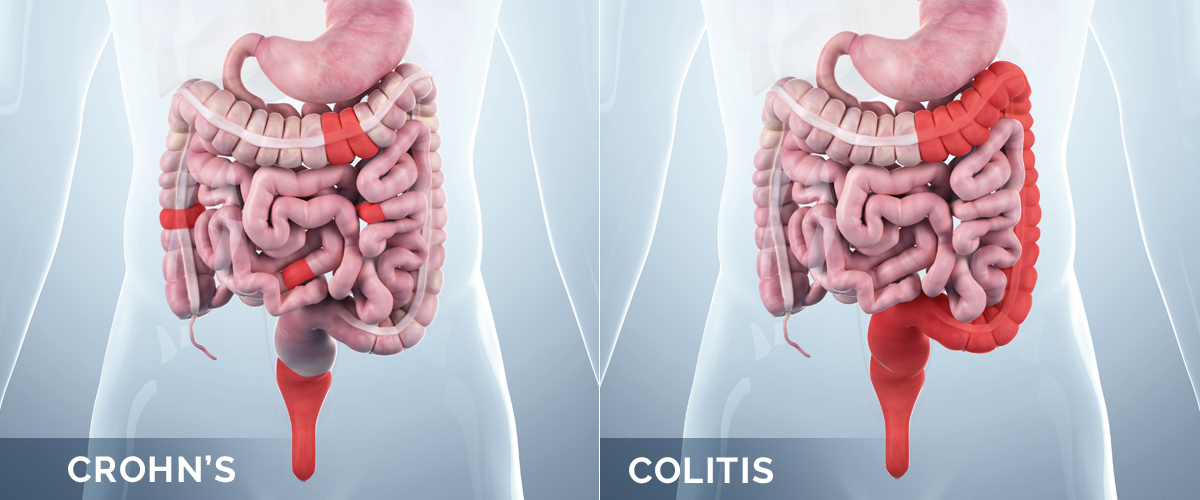

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD. In Crohn’s a patch or patches of the GI tract become temporarily reddened, swollen, and painful. Most often it is felt in the ileum of the small intestine but can be experienced in any part of the GI tract. Crohn’s flare-ups can affect the entire thickness of the bowel wall. The inflammation can even spread to areas of the body outside the gut. The inflammation can be quite debilitating.

Causes

It is unclear why Chron’s disease occurs. Genetics and environmental factors play a key role in flares.

Risk Factors

There are no general risk factors for Chron’s, though it appears it can be inherited. It can happen to anyone at any age. Most initial diagnoses occur in adults and adolescents. Flares can occur gradually or come on suddenly. Caregivers should watch for flare-up signs of:

- Diarrhea

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Blood in your stool

- Mouth sores

- Reduced appetite and weight loss

- Pain or drainage near or around the anus due to inflammation from a tunnel into the skin (fistula)

Ulcerative Colitis

Another IBD is ulcerative colitis (UC). It differs from Chron’s disease in that it affects only the innermost layer of the colon and rectum. Unlike the patchiness of Chron’s, UC uniformly involves large portions of the colon and rectum.

Doctors will classify UC occurrences by where it is located and label them accordingly. The different names can cause caregivers to think a different disease is occurring, which can lead to some confusion for caregivers. If you see the following names, remember, it’s actually ulcerative colitis.

- Ulcerative proctitis

- Proctosigmoiditis

- Left-sided colitis

- Pancolitis

Ulcerative colitis symptoms most often are mild to moderate and usually develop over time. If left untreated, UC can lead to holes in the lining of the colon wall. Caregivers should watch for:

- Diarrhea, often with blood or pus

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Rectal pain

- Rectal bleeding — passing small amounts of blood with stool

- Urgency to defecate

- Inability to defecate despite urgency

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Fever

- In children, failure to grow

|

Interesting Fact

The inflammation that occurs in inflammatory bowel diseases can spread outside of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammatory symptoms and the accompanying pain occurs in the skin, joints, and eyes during IBD flareups.

|

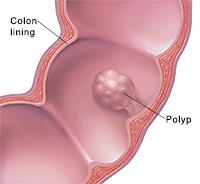

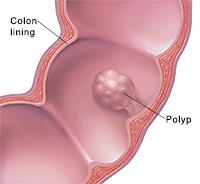

Polyps and Colorectal Cancer

Colon polyps are a small group of cells that have grown abnormally. They form bumps or mushroom-like stalks in the inside lining of the large intestine, rectum, and other places in the body. Most polyps are benign, meaning that they are non-cancerous. Unfortunately, there is always the potential of cancer developing over time, usually after many years, especially if the polyps are larger. Anyone can develop polyps, but you are more like to have them if you are older than 50, a smoker, obese, have a family history of occurrence, or have a history of colon cancer.

Colon polyps are a small group of cells that have grown abnormally. They form bumps or mushroom-like stalks in the inside lining of the large intestine, rectum, and other places in the body. Most polyps are benign, meaning that they are non-cancerous. Unfortunately, there is always the potential of cancer developing over time, usually after many years, especially if the polyps are larger. Anyone can develop polyps, but you are more like to have them if you are older than 50, a smoker, obese, have a family history of occurrence, or have a history of colon cancer.

Causes

Abnormal growth sometimes happens without any discernable cause; other times, repeated cell damage or chronic inflammation triggers their growth. Other known causes are:

- A foreign object

- A cyst

- A tumor

- Mutation in the genes of the colon cells

- Toxin exposure to such substances as tobacco and alcohol

Signs and Symptoms

Most polyps appear without any outward signs or symptoms. If they turn cancerous or become large enough to cause obstruction, the following symptoms may occur:

- Blood in stool

- Abdominal pain

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

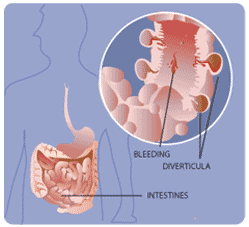

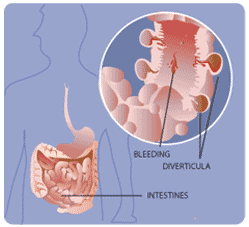

Diverticular Disease

Diverticular disease is the manifestation of diverticula in the colon. Diverticula are the opposite of polyps. They are outpouching pockets, small sacs that develop at weak points in the colon wall. Diverticular disease presents itself in a severity spectrum based on symptom presentation. On the mild side you have diverticulosis, which is a common condition of diverticula without any outward symptoms. Mid-range is diverticula, in which one develops holes that bleed into the stool. On the severe side you have diverticulitis, where the holes have developed painful infections.

Diverticular disease is the manifestation of diverticula in the colon. Diverticula are the opposite of polyps. They are outpouching pockets, small sacs that develop at weak points in the colon wall. Diverticular disease presents itself in a severity spectrum based on symptom presentation. On the mild side you have diverticulosis, which is a common condition of diverticula without any outward symptoms. Mid-range is diverticula, in which one develops holes that bleed into the stool. On the severe side you have diverticulitis, where the holes have developed painful infections.

Causes

Diverticula are thought to be caused by the extra pressure exerted from repeated bouts of constipation. Increased constipation is most commonly caused by dehydration or a poor diet that is high in fat and low in fiber. Old age is also a contributing factor.

|

Interesting Fact

It is a common myth that eating seeds and nuts causes diverticulitis, but there’s no actual proof that this actually occurs.

|

Signs and Symptoms

- Lower abdominal pain

- Fever

- Rectal bleeding

Risk Factors

- Aging, especially after age 40

- Obesity — increased pressure on the gut

- Smoking

- Lack of exercise — lower muscle tone creates weaknesses

- Diet high in animal fat and low in fiber

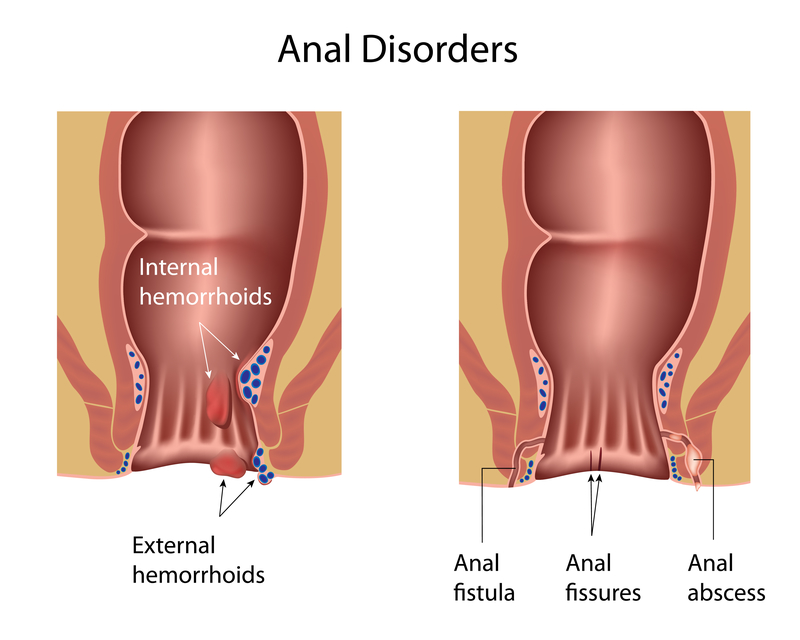

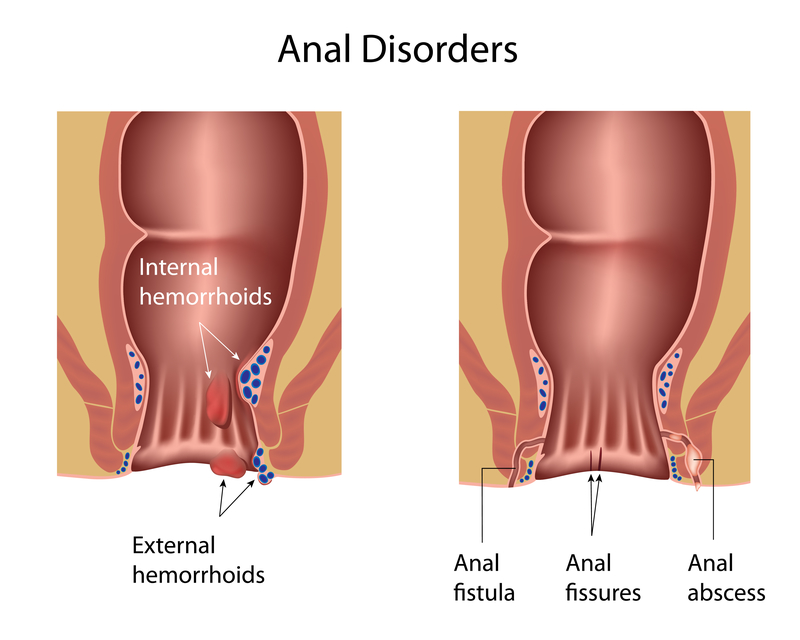

Hemorrhoids and Anal Fissures

Hemorrhoids are swollen and inflamed veins in the lower rectum and anus. Anal fissures are small tears in the lining of the anus. Hemorrhoids are a common occurrence in older adults and are sometimes called piles. Anal fissures may be seen in newborns and infants. The irritation that is felt may lead to anal sphincter spasms.

Causes

Occurrences are plainly a matter of too much pressure on weakened tissues. The extra pressure and tissue weakness has varying causes. Sometimes the cause is unknown; sometimes it’s just a matter of standing too long. Other known contributing factors are:

- Aging

- Chronic constipation or diarrhea

- Pregnancy

- Heredity

- Straining during bowel movements

- Faulty bowel function due to overuse of laxatives or enemas

- Spending long periods of time on the toilet (e.g., reading)

Risk Factors

- Aging

- Obesity

- Chronic inflammatory conditions

|

Interesting Fact

Hemorrhoids are common in both men and women and affect about 1 in 20 Americans. About half of adults older than age 50 have hemorrhoids.

|

Source https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/hemorrhoids/definition-facts

Malabsorption Syndromes

Malabsorption syndromes are a group of disorders that affect absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. They either result from improper digestion of food or a disturbance in the absorption process. The result is the same: malnutrition. It can be a temporary condition (like the recovery time after a surgery) or a permanent problem that has long-term consequences.

Malabsorption causes diarrhea, weight loss, and bulky, extremely foul-smelling stools. It throws off the balance in the gut garden and makes your resident chronically feel bad.

Causes

For the most part, this is a secondary condition that is being caused by other things. Just about every disease listed in this section, bad genes, or a completely unknown cause could be contributing factors.

Risk Factors

Caregivers of the developmentally challenged and the chronically ill should keep an eye on the overall gut health of the resident. It is going to require a more intense focus on the diet of the resident. In this case, food (or the nutritional elements in the food) becomes therapy.

Food Allergies and Intolerances

Two of the causes of malabsorption are food allergies and food intolerances. They can have similar symptoms but are really two different conditions. The real difference between them is in the consequences of long-term exposure to the offending food type.

Food Intolerances are the result of the body being unable to digest a specific food properly. Part of the digestive system is missing or broken. The most well-known is lactose intolerance. The patient’s body does not produce lactase, an enzyme that is required to break down some of the proteins in dairy products. The result is the undigested protein flows into the colon, creating a food source for bacteria. The bacteria love it. They eat it all and produce byproducts that result in the symptoms that the patient feels. An example is CO2, which builds up and causes bloating and flatulence (farting).

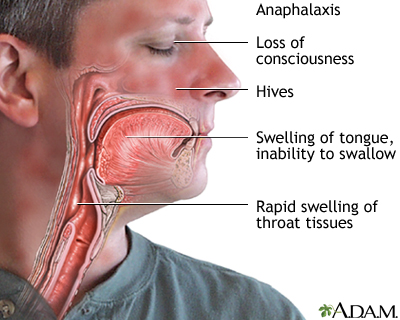

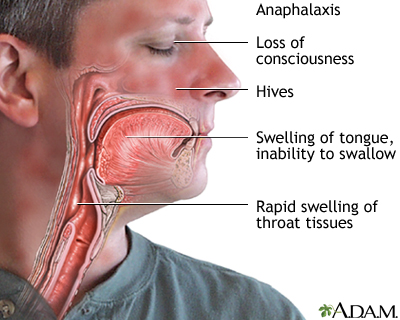

Food allergies are the result of an overreaction of the immune system. When exposed to a certain food, the immune system thinks that the body is being invaded by a foreign substance and triggers inflammation. The inflammation shows as redness, rash, itching, swelling, and fever. Since all this is happening on the inside as well as the outside, the patient can also experience nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

The Difference: Consequences of Exposure

The difference between food intolerance and allergy is how much inflammation there is. In food intolerance, a small amount of food causes little or no reaction. In a true allergy, even a microscopic amount of food breathed into the lungs can trigger a full-blown reaction. Also, the more exposure to the food (allergen), the more severe the response can get. That includes the lungs swelling up inside, causing breathing difficulties and death (anaphylaxis).

For caregivers, the difference between the two is crucial in managing the diets of their residents and what to do after exposure happens.

|

Interesting Fact

90% of human food allergies are the following:

- Cow’s milk

- Soy

- Eggs

- Wheat

- Fish and shellfish

- Peanuts and tree nuts

|

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome is a condition where the patient experiences a certain set of symptoms. Doctors call it a syndrome because no one knows what causes these symptoms and there are no medical tests that can be used in diagnosing what is going wrong. It all comes down to the skill of the doctor in recognizing the following symptoms as IBS.

- Abdominal pain, cramping, or bloating that is typically relieved or partially relieved by passing a bowel movement

- Excess gas

- Diarrhea or constipation — sometimes alternating bouts of diarrhea and constipation

- Mucus in the stool

You’ll notice that the list is very general. A lot of other gut problems could cause those symptoms. What most doctors end up doing is running a bunch of tests that eliminate all other possible causes. If no other conditions exist, then they call it IBS. That is why I left IBS for last. It helps you understand what a doctor has to go through before he can say someone has irritable bowel syndrome.

Causes

Even though the cause of IBS is still unknown, researchers strongly suspect that:

- The muscle contraction mechanism is involved. Muscle contractions that are stronger and last longer lead to gas, pain, and diarrhea. Muscle contractions that are weaker lead to constipation.

- Something has gone wrong with the nervous system and the GI tract. You remember the gut-brain axis?

- The gut’s microbiome is a contributing factor. It’s either a communication problem, an imbalance, or something yet unknown.

- Environmental factors can trigger an episode. For example, food intolerances or allergies can cause an IBS flare.

- IBS is not caused by stress, but stress can make symptoms worse.

|

Interesting Fact

Women are twice as likely to experience symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. It is thought that hormones may play a role in IBS.

|

Risk Factors

Irritable bowel syndrome is not a serious or life-threatening condition. So far, no long-term consequences have been reported. There is a very small risk of it contributing to the severity of other GI pathology. However, it can seriously impact a patient’s wellbeing and quality of life. You can imagine what it would feel like to suddenly have a painful spasm in your lower abdomen. In fact, doctors used to call IBS a spastic colon. Identifying and managing triggers becomes a major part of therapy.

Caregivers and GI Pathology

You are now even higher on the digestive system learning curve. You have a broader base of knowledge and are more capable of understanding what’s behind the abdominal difficulties that your residents are experiencing. Communications with other health professionals should be that much easier as well. It’s kind of hard not to feel foolish when you don’t have the foggiest idea what’s going on. You should now have more confidence in asking the right questions and understanding at least some of the answers.

We’re not done with the learning yet. Let’s get you even higher on the digestive system learning curve and cover the topic that really matters to in-home caregivers: GI caregiving expertise.

Gastrointestinal Caregiving

The same symptoms for so many conditions

There are only so many ways the body can signal that something is going wrong. For example, if a resident’s colon has Chron’s disease, or lactose intolerance, or inflammatory bowel disease, it’s going to feel bloated, painful, and have diarrhea. Same symptoms, different conditions … because they all involve the colon. Easy enough to understand. I’m going to take advantage of that fact and make this course easier for you. I’m going to lump all the caregiving concepts of all the conditions as if they were all the same, with a few notes on subtle differences in between diseases when applicable. So let’s get to it.

|

Interesting Fact

About 60 to 70 million Americans are affected by digestive diseases.

|

Prevention

The easiest way to take care of a malady from a caregiving point of view is to prevent it from happening in the first place. I know foster care providers can’t do much in preventing diseases from occurring. Genetics, environmental factors, and lifestyle choices have all occurred way before the resident moves into your home. The damage has already been done.

But, the patient is now in your home and you are in control of the environmental factors and lifestyle choices. You can help the resident live a healthy lifestyle that will have a big impact on symptom flare-ups. It’s what foster care providers do better than any another health professional.

Caregiver Tips to Maintain a Healthy Gut

- Reduce stress. A calm, content resident is an easier resident to take care of. That includes reduced abdominal issues.

- Eliminate the obvious symptom triggers. No smoking, no alcohol, reduce caffeine intake, limit spicy foods, reduce fatty and processed foods, and control exposures to allergens.

- Walks are my preferred mode of keeping the resident moving. Couch potatoes are more likely to require more caregiving efforts in the long run, not less. Kind of ironic, isn’t it.

- Plenty of fluids. The digestive highway is a road paved with water.

- Be mindful of how the whole body works. Engage in holistic caregiving. Take advantage of aromas to stimulate appetite. Include residents’ favorites in the menu. Pay attention to food textures. Encourage slower eating habits and chewing properly. Eating too fast and swallowing big chunks can trigger symptoms.

- Eat on a schedule. It’s easier for the cook, and better for the resident.

Monitoring

Foster care providers are the eyes and ears of the doctor. More than any other health professional, they are in the best position to tell when things are going wrong. That is what it all boils down to: recognizing what is different. Establish a routine and start to pay attention when the resident deviates from the norm. Once the behavior has got your attention, look for patterns. Don’t get excited about one-offs. Look for repeating symptoms, except when it’s severe. Start keeping notes so that you can pass on the important details to the doctor. Don’t worry about figuring out what is going on; that’s what you pay the doctor for. Your role is the attention-getting red-flag-waver. If you do recognize something the doctor isn’t paying attention to, the most diplomatic way to handle it is by asking pointed questions. For example, “Doctor, I noticed that my resident gets an upset stomach after eating dairy, but I could not see any evidence of inflammation or a rash. Do you think it’s lactose intolerance?”

The overriding principle for all foster care monitoring is “When in doubt, call it out.” And keep calling it out until you’re satisfied with the answer or outcome. When you “call it out,” have some data to support your concern or no one will pay attention to you in the future.

|

Interesting Fact

Most caregivers use a menu. It’s the most efficient and cost-effective way of feeding everyone. Did you realize that the menu can also be used as a food/symptom diary? Pretty cool, isn’t it? Paying attention to how the resident reacts to the menu steps up your monitoring and recordkeeping with hardly any extra effort.

|

Diet/Nutrition

Simply put, diet is what you serve your residents and nutrition is what your residence absorbs. In GI disorders, they aren’t necessarily the same. There are many conditions that prevent the absorption of vital nutrients. As a caregiver/cook, malnutrition is something to be concerned over. The question is, does your resident get enough of the right foods? On the other hand, certain foods are triggers for symptoms. So, the flipside of the issue is, what foods are you giving too much of?

Now we’re crossing over into a foster care therapy twilight zone. The questions are:

- When does food become therapy?

- How much do you involve the doctor in planning the menu?

Fortunately, I found the answers in doing my research for this course. The answer to question 2 first: There is no special diet for any given disease. There are just too many variables to establish a “one menu fits all” diet. It’s all a matter of taking what you’re cooking and tweaking it according the needs of the resident.

Now here’s the answer to question 1: In my experience, doctors don’t spend a whole lot of time counseling on menu choices. But, if they do write something down and hand it to you, food has become therapy. You’re required to adjust your cooking accordingly.

In these cases, my advice for caregivers/cooks is to cook from scratch. It gives you a lot more control in dealing with special needs. Instead of having to cook two separate meals, you just tweak the ingredients in a dish or adjust a smaller portion of a dish to meet the needs of therapy.

Cooking from scratch also has the benefits of avoiding preservatives and food additives, as many are known triggers of GI symptoms. It’s also cheaper — you make more profit that way. You can regain some of the convenience lost in cooking from scratch by doubling or tripling the batches and freezing the leftovers. Ta-da, instant meal. Slow cookers are also a great way to cut the labor of home cooking.

General Dietary Guidelines for GI Disorders

- Fats – Fatty foods are harder to digest. They also trigger the bowel’s muscles to contract harder to move the food through. Both are bad things for all the inflammatory GI conditions. But we like fat. Our body craves it; it’s in our genes. Don’t try to eliminate fat, just cook smarter. Lean meats, trim that big hunk of fat off the pork roast, and cook with more olive oil. Here’s a trick I learned: instead of cooking veggies in butter, try chicken bouillon in water. It’s just as savory. During severe flare-ups it’s best to go fat-free.

- Fiber – Fiber is the part of the plant foods you eat that can’t be digested and absorbed. It just passes straight through your gut. Fiber increases the weight and size of your stool and softens it. The result is a bulky stool that triggers peristalsis, making it easier to pass through the gut. It’s good for chronic constipation, but bad for an inflamed colon. It’s a balancing act between the two conditions. A couple of ways to adjust the menu are: Leave the skins on fruits and veggies for more fiber, and off for less. Processed foods for less fiber, unprocessed foods for more. Examples: white bread vs. whole grain, applesauce vs. a raw apple, grape juice vs. grapes. If you use bulk fiber, you’ve got to keep hydrated or it will cause constipation.

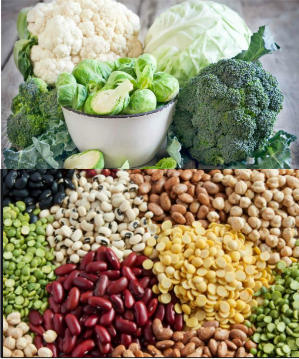

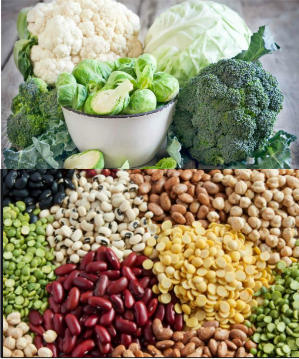

- Foods that cause gas – We can’t digest fiber, but our gut biome can. Good for our garden, which is good for us. Bad for GI problems because a side effect is CO2 gas. Bloating doesn’t feel too good and can be a symptoms trigger. We won’t even talk about the smell. Here is a list of foods that are more likely to cause issues for compromised guts.

- Beans

- Cabbage

- Legumes (like peas, peanuts, soybeans)

- Cauliflower

- Broccoli

- Lentils

- Brussels sprouts

Source: https://www.aboutibs.org/ibs-diet/foods-that-cause-gas-and-bloating.html

|

|

A final note about gas: Some sugar-free candies and desserts are sweetened with sweeteners that we can’t digest but bacteria can. The result? Too much sugar-free chocolate candy equals more gas and diarrhea. Bad for symptom flares.

|

Interesting Fact

The average person passes gas 14 to 23 times a day.

|

During symptom flare-ups, residents are understandably not going to want to eat. Here are a few menu suggestions that might help.

Cream of Wheat and Cream of Rice are well tolerated.

During vomiting and diarrhea episodes, electrolyte drinks like Gatorade or Pedialyte replace lost fluids and minerals.

Meal replacement drinks like Ensure and Boost give a lot of nutrition in a small drink. You can pack even more nutrients in a drink by adding Carnation Instant Breakfast to the glass. Use with skill because so much at once might be a symptom trigger.

There are a lot of good food replacements for when wheat and dairy products are an issue: rice milk, soy milk, rice pasta, almond flour, brown rice flour, etc. Check out the gluten-free section of the grocery store for more ideas.

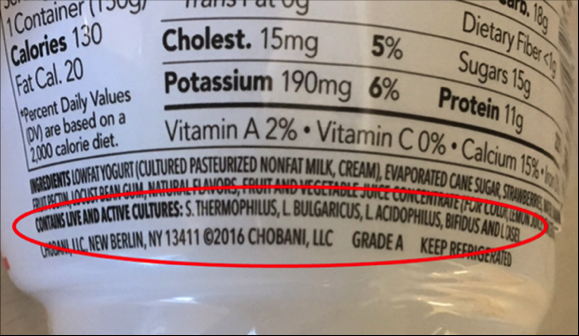

- Probiotics and Prebiotics

Probiotics are bacterial and yeast cultures and prebiotics are the material that they feed on. You get them as a supplement and in certain foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, tempeh, kimchi, pickles, buttermilk, and certain cheeses. It is tempting to say that probiotics are the good bugs of our microbiome, but that all depends on what’s needed. As you now know, the microbiome and body interaction is very complex. Check out my other CE on the subject.

There is just too much info to cover all dietary considerations of each condition. I’ll stop here, with one last tidbit of advice: Whatever you do, ease into it. Gradually introduce things like fiber and probiotics into the menu. Let the resident’s gut get used to the new conditions slowly. If you need more info, here are a few sites that will get you started. You can always get more info from the doctor as well.

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/15637-gastrointestinal-soft-diet-overview\

- https://www.nutrition.gov/diet-and-health-conditions/digestive-disorders

Doctors

Doctors

Dealing with doctors and digestive system pathology can be kind of frustrating for caregivers. The doctors don’t always act the way you want them to. It helps to remember that doctors are facing the same dilemma as you are when trying to diagnosis GI problems: so many diseases with the same symptoms. The only way for the doctor to figure out what is going on is by asking a lot of questions and doing some tests. So, prepare yourself, the resident, or the resident’s family. I suggest you answer these questions before the doctor’s visit.

- What symptoms is the resident experiencing?

- Is there blood involved?

- Is there bowel habit disruption?

- When did you first begin experiencing symptoms?

- Have your symptoms been continuous or off and on? Give time frames.

- How severe are your symptoms? (Scale of 1–10, 10 being the worst.)

- Do your symptoms affect your ability to do activities of daily living (ADLs)?

- Does anything seem to improve your symptoms?

- Is there anything that you've noticed that makes your symptoms worse?

- What is the overall effect of the symptoms on the quality of life of the resident? (sleep disruption, low appetite, depression etc.)

Remember to follow up with the doctor, especially if there is a new diagnosis and/or new therapy. If the doctor does not hear from the patient, he will most likely assume that everything is okay. Work with the doctor in establishing a new “normal” life for the resident. Keep at it until YOU are satisfied. YOU are the in-home caregiving expert and patient advocate, not the doctor.

|

Interesting Fact

About 70 percent of people with Crohn’s disease eventually require surgery. Different types of procedures may be performed depending on the reason, severity of illness, and location of the disease. Approximately 30 percent of patients who have surgery for Crohn’s disease experience recurrence of their symptoms within three years and up to 60 percent will have recurrence within 10 years.

|

Conclusion

You are now higher on the GI tract learning curve. Hopefully your knowledge base is broad enough to handle any problem your resident’s digestive system can dish out. I can honestly say with a straight face that you as a caregiver are now better prepared to follow your gut reactions in caring for your resident’s guts.

References:

Probiotics: What You Need To Know. National Center for Complementary and Integrated Health, NIH. 2019 https://nccih.nih.gov/health/probiotics/introduction.htm

Peter Jaret. Secrets to Gas Control. WebMD. Sept. 17, 2012 https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/features/secrets-gas-control#1

Food intolerance versus food allergy. American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology. 2019. https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/food-intolerance

Anal fissure. MayoClinic. 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anal-fissure/symptoms-causes/syc-20351424

Diverticulitis. MayoClinic. 2019.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diverticulitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20371758

Diverticular Disease. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. 2019. https://www.fascrs.org/patients/disease-condition/diverticular-disease

Gastroparesis. Cleveland Clinic. 07/02/2018. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15522-gastroparesis

Ulcerative colitis. MayoClinic. 2019.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ulcerative-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20353326

Overview of Crohn's Disease. Crohns and Colitis Foundation. 2019. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-crohns-disease/overview

Crohn's disease. MayoClinic. 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/crohns-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353304

Digestion: How long does it take? MayoClinic. 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/digestive-system/expert-answers/faq-20058340

Gut microbiota info. Gut Microbiota for Health. 2019. https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/en/about-gut-microbiota-info/

The Brain-Gut Connection. Health. Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2019. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/the-brain-gut-connection

https://www.drugs.com/article/gastrointestinal-disorders.html

Gastrointestinal Disorders. Drug.com Mar 20, 2019. https://health.usnews.com/health-news/articles/2012/09/06/8-common-digestive-problems-and-how-to-end-them

GI Disorders. Internamtional Foundation of Gastrointestenal Disorders. Oct. 2 2019.https://iffgd.org/gi-disorders.html

Matthew Hoffman, MD. Picture of the Stomach. WebMD. March 07, 2018. https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/picture-of-the-stomach#1

Kristeen Cherney. Understanding Digestion Problems. Healthline. June 18, 2018. https://www.healthline.com/health/digestion-problems#ibd

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Healthline. Sept. 28, 2018. https://www.healthline.com/health/inflammatory-bowel-disease

Valencia Higuera. What is Ulcerative Colitis? Healthline. Jan. 23, 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/ulcerative-colitis

Kimberly Holland. Understanding Crohn’s Disease. Healthline. May 2, 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/crohns-disease

Michael Kerr, Kristeen Cherney. The Difference Between Crohn’s, UC, and IBD. Healthline. Dec. 2, 2019 https://www.healthline.com/health/crohns-disease/crohns-ibd-uc-difference#diagnosis

Gastrointestinal tract. Wikipedia. Nov.25 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastrointestinal_tract

Gastrointestinal system anatomy. Healthengine. Jan.30 2006. https://healthengine.com.au/info/gastrointestinal-system

Kim Maryniak, PhD. The Gastrointestinal System. RN.com 2019. https://www.rn.com/clinical-insights/gastrointestinal-system/

The Structure and Function of the Digestive System. Cleveland Clinic. Sept/13/2018.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/7041-the-structure-and-function-of-the-digestive-system

Slide show: See how your digestive system works. MayoClinic Sept. 27, 2018. https://www.mayoclinic.org/digestive-system/sls-20076373?s=3

Human digestive system. Wikipedia. Oct.18 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_digestive_system

Gastrointestinal tract. Wikipedia. Nov.25 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastrointestinal_tract

Celiac disease. WebMD. 2019. https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/celiac-disease/celiac-disease#1ttps://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/celiac-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20352220

Exam Portal

click on [Take Exam]

Purchase membership here to unlock Exam Portal.

*Important*

Registration and login is required to place your name on your CE Certificates and access your certificate history.

Username MUST be how you want your name on your CE Certificate.